The God Who Was Warned He Would Die

The crowd roared as the chariot rolled through the Porta Triumphalis, the gate used only for this purpose. Flower petals drifted down. Every temple in Rome stood open, their doors thrown wide to share in the spectacle. And at the center of it all, a man stood draped in purple and gold, his face painted the color of blood.

For this single day, Lucius Aemilius Paullus was permitted to be a god.

Behind him, a slave held a golden crown over his head. According to tradition, this slave whispered continuously into the general's ear: "Respice post te. Hominem te memento." Look behind you. Remember you are a man.

It was September 167 BCE. Paullus had just destroyed the last remnant of Alexander the Great's empire. He had dragged a king through Roman streets in chains. He had brought home treasure beyond calculation. And in less than two weeks, he would bury both of his remaining sons.

The Roman triumph was the highest honor a general could receive. It was also a ceremony shot through with reminders of death, fragility, and luck. What it tells us about Roman anxieties is as revealing as what it tells us about Roman power.

What It Took to Earn a Triumph

Not every victory warranted a triumph. The Senate controlled access, and their standards were specific.

A commander seeking a triumph needed to hold imperium, the supreme military command granted only to consuls, praetors, or dictators. He had to have won a decisive land or sea battle, not merely a skirmish or siege. Ancient sources suggest he needed to have killed at least 5,000 enemy combatants, though enforcement of this threshold varied. Most importantly, the war itself had to be over. No ongoing campaigns. No loose ends. The enemy had to be finished.

Politics mattered as much as military success. A commander who entered Rome before his triumph was formally granted forfeited his claim. That was it. Done. Cicero, returning from his governorship of Cilicia, lingered outside the city walls for weeks, hoping in vain for a triumph that never came. The moment he crossed the pomerium, the sacred boundary of the city, his military authority ended. For a man who had crushed a kingdom, patience was the final test.

Once the Senate voted approval, the commander became the triumphator. For a few hours, he would be elevated above other mortals. This is why the Romans surrounded the ceremony with so many reminders of human limitation.

The Procession: A Three-Day Spectacle

Paullus's triumph lasted three days, each devoted to a different aspect of his conquest. Ancient historians lingered on the details, recognizing this as a turning point in Roman history.

On the first day, 250 wagons rolled through the streets carrying the artistic treasures of Macedonia. Statues looted from Greek temples. Paintings from royal palaces. Bronze armor and gilded weapons. The accumulated wealth of the Hellenistic world, wheeled past crowds.

The second day belonged to Macedonian arms. Not thrown together carelessly, but arranged by artisans to create the illusion of heaped battle trophies. The famous Macedonian sarissas, the eighteen-foot pikes that had conquered the known world under Alexander, lay broken and piled like kindling. Round bronze shields caught the sun. The most feared military power of the previous century had been dismantled.

On the third day came the human element. First, the captive Macedonian aristocrats, their faces heavy with grief. Then the king's children, too young to fully understand their fate but old enough to weep. And finally, King Perseus himself.

He wore a dark robe and the high boots of Macedonian royalty, but everything about his posture spoke of defeat. Ancient sources describe him as "dumbfounded and bewildered," walking like a man who had already died. Behind him came his former courtiers and generals, men who had once commanded armies, now shuffling through foreign streets toward whatever came next.

The Triumphator's Regalia: Dressed as a God

What made the triumph visually overwhelming was the triumphator himself. For this single day, he dressed in the regalia of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Rome's supreme deity.

The toga picta was entirely purple, embroidered with gold, a garment otherwise forbidden to Roman citizens. Purple dye, extracted laboriously from murex sea snails, was the most expensive substance in the ancient world. To wear solid purple was to wear a fortune. The tunic beneath was the tunica palmata, decorated with palm leaves, another symbol of victory.

The triumphator's face was painted with red lead or vermillion, giving him the ruddy complexion attributed to Jupiter in ancient cult statues. This was not metaphorical. For the duration of the procession, the general ritually became the god. He held an ivory scepter topped with an eagle, Jupiter's sacred bird. He carried a laurel branch, symbol of victory and purification.

The four white horses pulling his chariot were unusual in themselves. White horses were rare in the ancient world; these animals would have been specially selected or imported. The chariot was gilded, covered with laurel wreaths. The entire ensemble was designed to overwhelm.

And behind this living god stood that slave, whispering mortality.

The Slave with the Golden Crown

The auriga, the slave who rode with the triumphator, represents one of the strangest elements of Roman ritual. Modern scholars debate whether this practice was as ancient and consistent as later sources suggest. The main account comes from Tertullian, a Christian writer of the second century CE, who may have been interpreting an older practice through his own theological lens.

But the concept fits Roman values regardless of its precise origins. The Republic was suspicious of individuals who accumulated too much personal glory. The kings had been expelled. Any man who reached too high risked becoming a tyrant. The whispered reminder served as a check on hubris.

The soldiers marching behind the chariot played a similar role. They were permitted, even expected, to sing ribald songs mocking their commander. They might reference his alleged cowardice, his romantic scandals, his physical flaws. Julius Caesar's soldiers reportedly sang about his rumored affair with King Nicomedes of Bithynia. This ritualized mockery was thought to avert the evil eye, deflecting jealousy and supernatural retribution that might strike a man at the height of his glory.

The Temple of Jupiter: Where Glory Met Sacrifice

The procession wound through the Forum, up the Via Sacra, and finally to the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus on the summit of the Capitoline Hill. Here, every triumph ended with sacrifice and surrender.

The triumphator mounted the temple steps, laid down his laurel branch, and offered two white oxen to Jupiter. The tokens of victory, the enemy standards, the captured crowns, sometimes the enemy commander himself, were dedicated to the god. Victory belonged not to the general but to Rome and Rome's gods. The individual was their instrument.

This explains why every temple in Rome stood open during a triumph. The ceremony was shared by the entire divine community. The gods witnessed their servant acknowledge that all glory derived from them.

After the sacrifices, the leading captives faced their fate. During the Republic, prominent enemy commanders were typically executed in the Tullianum, the ancient prison at the foot of the Capitoline. This was not hidden; it was expected. The triumph celebrated not just victory but annihilation. The enemy king who had challenged Rome would not live to challenge again.

Perseus: The Last King of Macedonia

King Perseus deserves more than a footnote. He was the last ruler of the Antigonid dynasty, the last heir of the generals who had divided Alexander's empire. His defeat at Pydna in 168 BCE didn't just end a war. It ended an era.

Perseus had inherited a kingdom still formidable in military terms. The Macedonian phalanx, that bristling wall of eighteen-foot spears, five rows deep, shields locked so tightly that a fallen man was immediately replaced by the soldier behind, remained the most feared formation in the Mediterranean world. It had been broken once before, at Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE, but on rough terrain that disrupted its alignment. On flat ground, it still seemed invincible.

At Pydna, that changed. The Romans exploited rough ground that disrupted the phalanx's alignment. Their short swords proved murderously effective in the close-quarter chaos that followed. Ancient sources estimate that 25,000 Macedonians died in a single afternoon. Perseus fled the field, eventually seeking sanctuary on the sacred island of Samothrace. He surrendered there, perhaps hoping for clemency.

He received a triumph instead.

The sources disagree on how Perseus died. According to Plutarch, the Romans executed him by sleep deprivation: guards woke him every time he began to drift off, until his body simply failed. This took place around 166 BCE, roughly a year after his humiliation in Paullus's triumph. Livy offers a gentler version: Perseus was held in comfortable captivity at Alba Fucens until he died of natural causes.

Either way, the kingdom of Macedon ceased to exist. Rome divided it into four separate republics, none permitted to interact with the others. When an adventurer named Andriscus claimed to be Perseus's son and attempted a restoration in 149 BCE, Rome crushed him and imposed direct provincial rule. Alexander's homeland became a Roman province.

The Price of Victory: 150,000 Enslaved

Between the battle and the triumph, Paullus received orders from the Senate that revealed Rome's capacity for systematic brutality.

The Epirotes, inhabitants of the region along the western Greek coast, had provided support to Macedonia during the war. The Senate decided to make an example. In 167 BCE, Paullus coordinated an operation of stunning logistical precision. Roman soldiers moved simultaneously against seventy towns in the Molosian region of Epirus. They reached each settlement on the same day, at the same hour. In a single morning, 150,000 people were enslaved.

Ancient sources portrayed this as somehow out of character for the "mild and generous" Paullus. The reality was simpler: this was within the range of normal Roman conduct toward populations that had placed themselves under Roman authority and then defied it. Mass enslavement was a tool of empire. After Pydna, the Roman slave trade operated on an industrial scale, feeding a demand for labor that would reshape Mediterranean society.

The soldiers who carried out these orders received surprisingly modest pay. Accounts suggest only 11 drachmas per man, despite the enormous value of the captured population. Their discontent would have political ramifications, but it did not prevent the operation itself.

When Fortune Turned: The Death of His Sons

Paullus had four sons. Following aristocratic custom, he gave his two eldest to other prominent families for adoption, one to the Fabii, one to the Scipios. The boy adopted by the Scipios would become Scipio Aemilianus, the future destroyer of Carthage. These adoptions strengthened political alliances while preserving family lines that might otherwise go extinct.

This left Paullus with two remaining sons, ages fourteen and twelve. The boys who would carry on his name. The heirs to his triumph.

Five days before the celebration began, the elder son died suddenly. Ancient sources offer no clear cause, perhaps illness, perhaps accident. The triumph proceeded regardless. Then, three days after the final ceremonies concluded, the younger son followed his brother.

Within two weeks, Paullus had gone from Rome's most celebrated general to a bereaved father burying his only remaining heirs.

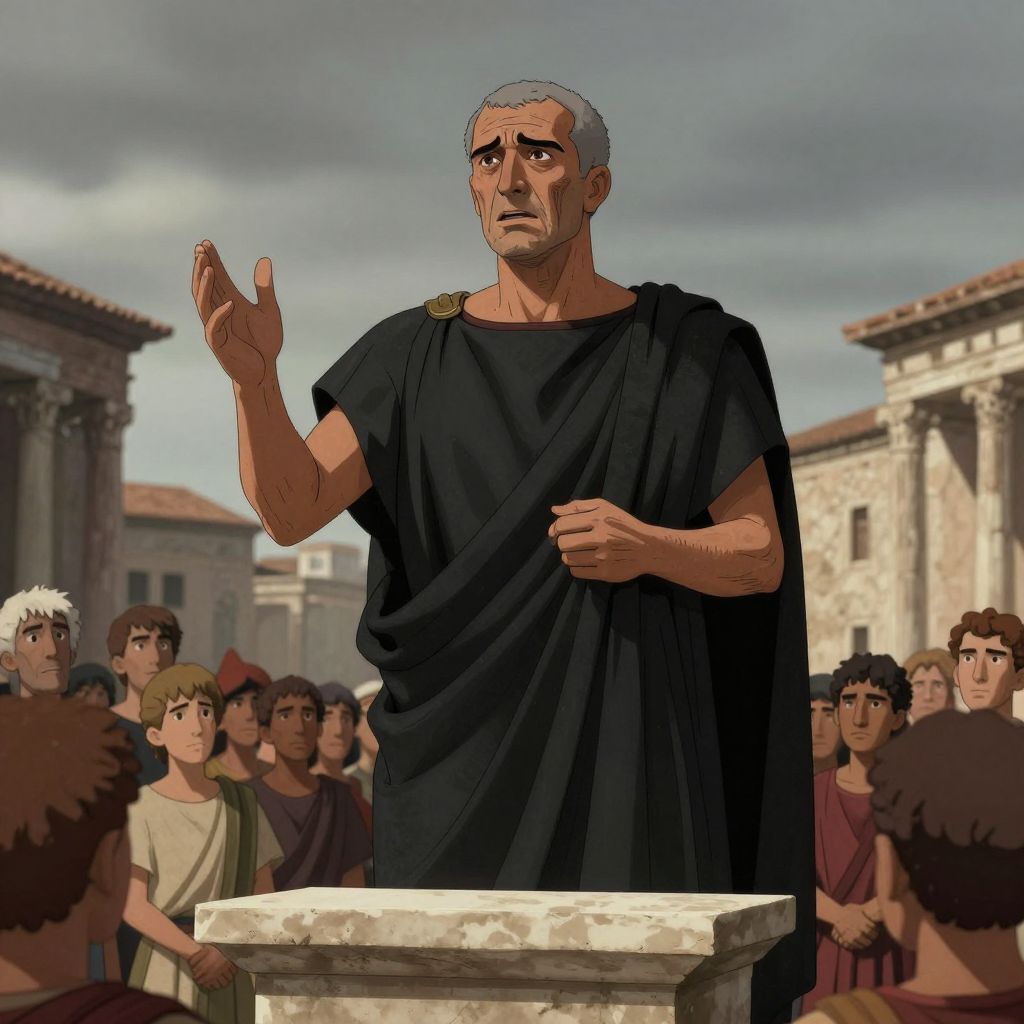

What he did next has echoed through two millennia of Western thought. Paullus called the Roman people to assembly. Standing before them, he delivered what would become one of the most famous speeches in Roman history.

He acknowledged that fortune had favored him in the Macedonian campaign beyond all reasonable expectation. No storms. No setbacks. No unexpected difficulties. He had suspected at the time that such smooth success would demand payment.

"I prayed," Paullus told the assembly, "that if any retribution was due for our good fortune, it might fall upon my house rather than upon the state."

The gods had granted his prayer.

This was Roman aristocratic ideology pushed to its limit. Duty to the state exceeded personal grief. The family existed to serve Rome, not the reverse. Paullus transformed his tragedy into a theological bargain: his sons had died so that Rome might prosper. Whether he truly believed this or was simply performing the role his culture demanded, we cannot know.

Polybius: The Historian Who Watched It All

Among the thousand Achaean nobles transported to Rome as hostages after Pydna was a cavalry commander named Polybius. He would spend seventeen years in Roman captivity. He would also become one of history's greatest historians.

Polybius was no ordinary prisoner. His education and intellectual sophistication attracted the attention of Roman aristocrats who prized Greek culture. He became attached to the household of Aemilius Paullus himself, eventually serving as tutor to Scipio Aemilianus, the adopted son who would one day complete Rome's conquest of Carthage.

His Histories, running to forty volumes, attempted to explain how Rome had conquered the known world in barely fifty years. Writing as both outsider and insider, captive and confidant, Polybius offered perspectives that purely Roman sources could not. His description of the triumph of Paullus provides some of our most detailed evidence for the ceremony.

The personal dimension was never far from his analysis. Here was a man who had commanded cavalry for the Achaean League, now forced to watch as Rome absorbed the Greek world into its imperial system. His survival strategy was intellectual: understand the conquerors, explain their success, make himself indispensable to their elite.

He succeeded. When the Achaean hostages were finally released in 150 BCE, Polybius remained close to Scipio. He was present at the destruction of Carthage in 146 BCE, watching as Roman soldiers erased a civilization that had challenged them for over a century. He returned to Greece after Corinth fell in the same year, using his Roman connections to moderate the terms of submission.

The Triumph as Imperial Theater

The Roman triumph served purposes beyond honoring individual commanders. It was propaganda, theology, and entertainment at once.

For the Roman people, it offered a rare opportunity to see the wealth of conquered nations with their own eyes. The treasures that normally remained abstract, "the king's gold," "the eastern luxuries," became concrete. Here were the statues. Here were the weapons. Here was the king himself, reduced to a shuffling captive. The crowd could touch empire.

For the Senate, the triumph reinforced collective authority over individual glory. The ceremony was granted, not claimed. The general processed through streets owned by the people, toward a temple of the state's gods, to surrender his victories to institutions greater than himself. However elevated the triumphator appeared, the message was clear: Rome made him, and Rome could unmake him.

For the soldiers, it offered compensation. They received a share of the plunder. They marched in procession. Their service was publicly honored. The ribald songs they sang preserved their agency. They remained citizens, not mere instruments.

And for the captives, it offered humiliation calculated to destroy. The enemy commander was displayed not as a worthy opponent but as a broken thing, a cautionary example of what happened to those who defied Roman power. His execution at the ceremony's end provided narrative closure. The threat was ended. Rome was safe.

The Long Shadow of Glory

The triumph that Paullus celebrated in 167 BCE marked a turning point. After Pydna, Rome faced no peer competitor in the eastern Mediterranean. The Greek world submitted, if not always gracefully. Carthage would be destroyed within two decades. Spain would take longer to pacify, but the outcome was never in doubt.

What Paullus could not foresee was how this very success would transform Rome itself. The vast wealth flowing into the city disrupted traditional patterns of landholding and labor. Slaves poured in; the 150,000 from Epirus represented only a fraction of the human chattel generated by Roman conquest. The old citizen-farmer army would eventually prove unsustainable. The ambitious generals of the late Republic would use triumph-hungry soldiers as private armies, turning the ceremony itself into a weapon of civil war.

By the time of Augustus, the triumph had been largely monopolized by the imperial family. Private generals were no longer permitted to celebrate their victories so publicly. The ceremony that had once expressed republican ideals became a tool of monarchy.

But in September 167 BCE, none of that had happened yet. Paullus rode his gilded chariot. The slave whispered his mortality. And somewhere in the crowd, a Greek hostage watched, already beginning to write the history that would explain this strange, brutal, magnificent civilization to the ages.

The hero of the triumph had become the paradigm of human frailty. Perseus, conquered, still had his children. Paullus, conqueror, did not. The gods had granted his prayer.

Frequently Asked Questions

1What were the requirements for a Roman triumph?

A commander needed to hold imperium (supreme military command), win a decisive battle killing at least 5,000 enemies, and completely end the war. The Senate had to approve the honor, and the general could not enter Rome until it was granted — doing so forfeited his claim.

2Why was the triumphator's face painted red?

The red face paint was meant to resemble the terracotta cult statues of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. For the duration of the triumph, the general ritually embodied Rome's supreme deity, wearing Jupiter's regalia including the purple toga and golden crown.

3Did a slave really whisper 'remember you are mortal' during triumphs?

This tradition, called memento mori, is described by later sources like Tertullian, but scholars debate whether it was an original Roman practice or a later interpretation. Regardless, the concept reflects genuine Roman anxiety about excessive individual glory.

4What happened to captured enemy kings during a triumph?

Prominent captives like King Perseus of Macedonia were paraded through Rome and typically executed afterward in the Tullianum prison. Some sources suggest Perseus was killed through sleep deprivation; others claim he was held in comfortable captivity until natural death.

5How many people were enslaved after the Battle of Pydna?

In 167 BCE, Romans simultaneously attacked seventy towns in Epirus, enslaving approximately 150,000 people in a single coordinated operation — punishment for the region's support of Macedonia during the war.

6Why did Aemilius Paullus give away two of his sons for adoption?

Roman aristocratic adoption was a political strategy. Paullus's son adopted by the Scipios became Scipio Aemilianus, who later destroyed Carthage. These adoptions strengthened alliances between powerful families and preserved family lines that might otherwise end.

Experience the Full Story

Hear the triumph of Aemilius Paullus narrated by Lumo — the immortal wolf who watched empires rise and fall.

Listen to Related Stories

Listen to the Full Story

Experience history through immersive audio lessons narrated by Lumo, your immortal wolf guide.