The Blade That Killed a Dictator

On March 15, 44 BCE, Marcus Junius Brutus drove his dagger into the body of Julius Caesar. The dictator had treated Brutus like a son. He had pardoned him after Brutus fought against him in the civil war. He had promoted him to praetor and promised him the consulship. Brutus repaid him with twenty-three stab wounds delivered by sixty conspirators on the floor of the Roman Senate.

The strange part isn't that Brutus killed Caesar. It's that he genuinely believed he was doing the right thing. Brutus was a philosopher, a devoted Stoic, a man who wrote treatises on virtue and corresponded with Cicero about ethics. He killed a man who loved him because he thought the Republic demanded it.

He was wrong about everything except the killing.

A Name Like a Millstone

Marcus Junius Brutus was born around 85 BCE into one of Rome's oldest patrician families. His ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, had founded the Roman Republic in 509 BCE by overthrowing the last king of Rome. According to tradition, the first Brutus later discovered that his own sons were plotting to restore the monarchy. He sentenced them to death and watched the execution without expression.

Romans treated this story like scripture. The first Brutus was the ultimate republican hero, the man who loved Rome more than his own children. His statues stood in the Forum. His sacrifice was held up as the standard for civic virtue.

For Marcus Brutus, this ancestor was less an inspiration than a burden. Throughout his life, people reminded him of what he owed to his bloodline. The comparisons started young and never stopped.

His uncle Cato the Younger made it worse. Cato was the most uncompromising republican of the era, a man who refused bribes in an age when everyone took them and who opposed any politician who accumulated too much power. Brutus grew up watching Cato live by rigid Stoic principles, and he tried to do the same.

Unlike most Roman aristocrats, Brutus actually believed in the philosophy he studied. He wrote about virtue. He debated ethics with Cicero. He tried to act on his principles. In hindsight, this made him dangerous. A cynic would have calculated the odds and stayed home on the Ides of March. Brutus was an idealist, and idealists make terrible political calculators.

The Problem with Being Forgiven

When civil war broke out between Caesar and Pompey in 49 BCE, Brutus joined Pompey's side. This was strange. Pompey had murdered Brutus's father years earlier during the political chaos of the 70s BCE. By any normal measure of Roman vengeance, Brutus should have wanted Pompey dead. Instead, he joined his father's killer because he thought Pompey represented republican government better than Caesar did.

After Pompey lost at Pharsalus in 48 BCE, Caesar pardoned Brutus immediately. Not just pardoned him but befriended him. Caesar appointed Brutus governor of Cisalpine Gaul and then urban praetor, one of the highest magistracies in Rome. He promised Brutus the consulship.

There was a rumor that Caesar was Brutus's biological father. Caesar had carried on an affair with Brutus's mother Servilia for years. The timing doesn't quite work, but Caesar seemed to believe it might be true, or at least he acted like it was. He treated Brutus like a son.

Caesar's forgiveness created a trap. The more favors Brutus accepted, the more he owed Caesar personally, and the harder it became to oppose him politically. For a Stoic who believed that duty to the state outweighed personal relationships, this was torture. Brutus spent years accepting promotions from a man he was increasingly convinced was destroying Rome.

Meanwhile, Caesar kept piling up honors. Dictator for life. His face on coins, something no living Roman had done before. Purple robes. Divine honors. The trappings of monarchy, even if he never took the title.

Sixty Men With Daggers

The conspiracy came together in early 44 BCE. Cassius Longinus, Brutus's brother-in-law, recruited most of the conspirators. Cassius had his own reasons to hate Caesar. He had been passed over for appointments and felt his military career had stalled. But Cassius knew the plot needed Brutus's moral authority. Without Brutus, it was just a murder. With Brutus, it was a political statement.

Cassius worked on Brutus carefully. Anonymous notes appeared on Brutus's praetorian chair: "Brutus, you are asleep" and "You are no true Brutus." Notes showed up on statues of the first Brutus too. Whether Cassius planted them or simply took advantage of genuine public sentiment, they worked. Brutus agreed to join.

Sixty senators signed on. They called themselves "Liberators" and assumed Rome would celebrate once Caesar was dead. They planned the assassination in detail. They did not plan anything about what would happen next.

This failure of imagination would kill them all.

The Ides of March

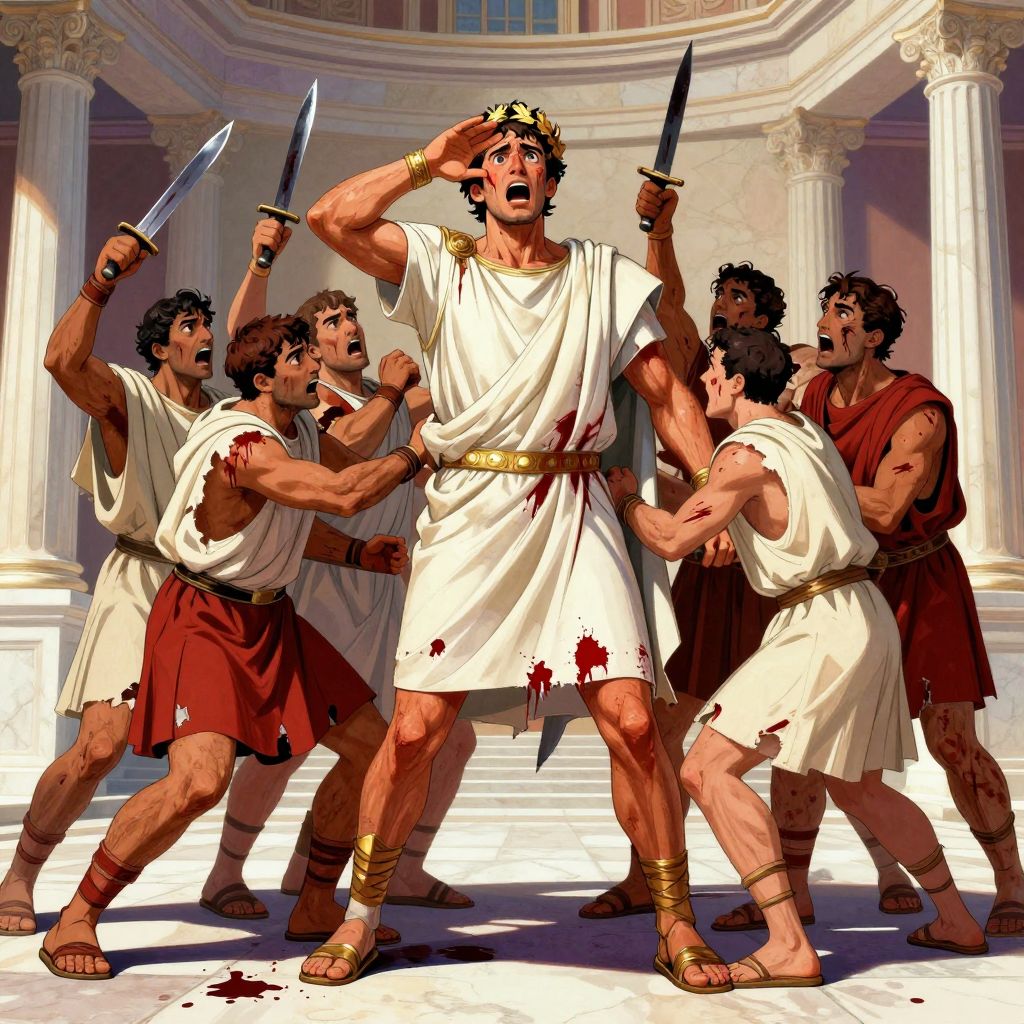

The assassination was messy. On March 15, Caesar arrived at the Theater of Pompey, where the Senate was meeting. A senator named Tillius Cimber approached with a petition for his exiled brother. When Caesar refused, Cimber grabbed his toga. That was the signal.

The conspirators came from all sides. In the confusion, they cut each other. Of Caesar's twenty-three stab wounds, only one was actually fatal. The rest were enthusiasm.

Caesar fought back at first, using his stylus as a weapon. Then he saw Brutus.

The famous last words may or may not have been spoken. Ancient historians disagreed. Some said Caesar spoke in Greek: "Kai su, teknon?" (You too, my child?). Others said he said nothing. Shakespeare gave him "Et tu, Brute?" which is memorable but probably invented.

What the sources agree on: when Caesar recognized Brutus, he stopped fighting. He pulled his toga over his face and fell at the base of a statue of Pompey. His old rival watched in marble as he died.

Silence Instead of Cheers

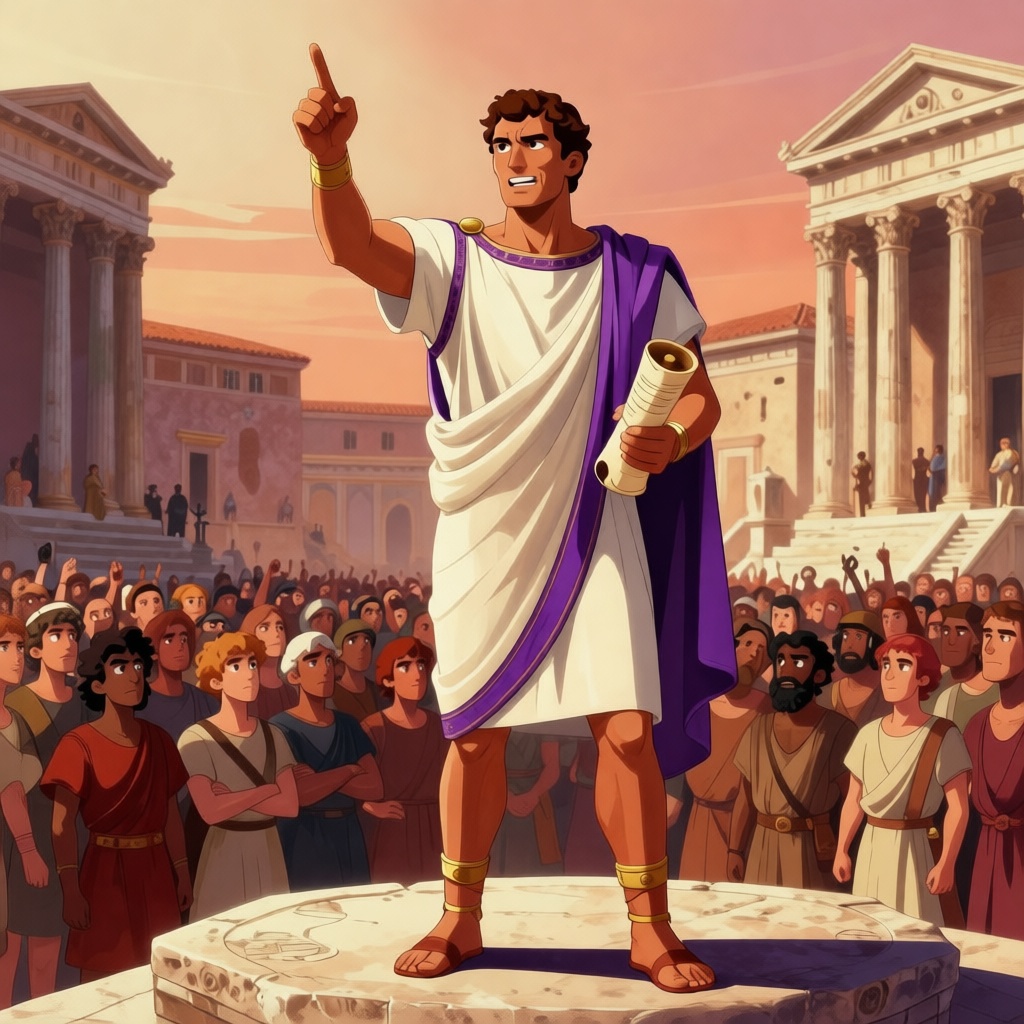

The conspirators ran out of the Senate expecting applause. They got nothing. Rome's doors locked. The "Liberators" wandered through empty streets waving bloody daggers and shouting about freedom. Nobody came out to celebrate.

This was the first sign that they had miscalculated everything.

Mark Antony seized control of the situation. At Caesar's funeral, he read the dictator's will aloud. Caesar had left money to every Roman citizen and bequeathed his private gardens to the public. Then Antony displayed a wax effigy of Caesar's body, rotating it slowly so the crowd could see all twenty-three wounds.

Antony never called the conspirators murderers. He just kept praising their "honor" until the word curdled into sarcasm. The crowd got the message. They burned Caesar's body in the Forum and then went hunting for the assassins.

Brutus and Cassius fled Rome within weeks.

The Republic's Last Army

For two years, Brutus and Cassius raised an army in the east. They gathered nineteen legions, one of the largest forces ever assembled for a Roman civil war. It was the last army that would fight for the Roman Republic.

Back in Rome, Octavian and Antony had formed the Second Triumvirate with a general named Lepidus. They published proscription lists: names of men who could be legally killed on sight, their property seized, their families ruined. Thousands of names appeared.

One of them was Cicero. The greatest orator in Rome had mocked Antony once too often. Soldiers caught him fleeing toward the coast. They cut off his head and his hands and nailed them to the Rostra in the Forum, the platform where he had given his most famous speeches.

The Republic's voice died nailed to a post.

In October 42 BCE, the armies met at Philippi in Macedonia. The first battle was a draw, but Cassius couldn't see that. From his position, all he saw was dust and chaos. He thought they were losing.

He killed himself. His side had actually been winning.

Of all the pointless deaths in Roman history, this one stands out. Cassius died for a misunderstanding.

The Last Night

Three weeks later came the second battle. Brutus's army broke. His allies ran. Everything he had believed in was finished.

That night, Brutus gathered his remaining officers. He quoted a line from Greek tragedy: "O wretched virtue, you were but a name, and I worshipped you as real."

The words are the saddest thing he ever said. Brutus had spent his entire life believing that virtue was real, that principles could guide action, that the Republic was worth dying for. At the end, he concluded that virtue was just a word. An abstraction. Something people talked about but that had no power in the real world.

He ran onto his own sword. Some say a friend held it for him.

The Noblest Roman

Mark Antony found the body. He stood looking at it for a long time. Then he did something unexpected. He took off his own purple cloak, the mark of a Roman general, and covered Brutus with it.

"This was the noblest Roman of them all," Antony said.

The tribute was sincere. Antony knew that Cassius had acted partly from jealousy. The other conspirators had various petty grievances. But Brutus had killed a man who loved him because he genuinely believed the Republic required it.

That he was wrong about what killing Caesar would accomplish didn't diminish what he had sacrificed to do it.

What Died at Philippi

Brutus's assassination of Caesar didn't save the Roman Republic. It destroyed any remaining chance of restoring traditional government. The power vacuum after Caesar's death led to more civil wars, more proscriptions, more destruction. Seventeen years after the Ides of March, Octavian stood alone. They gave him a new name, Augustus, and the Republic became the Empire.

Brutus remains a contested figure. Dante put him in the lowest circle of Hell, alongside Judas, as a traitor to his benefactor. The American revolutionaries saw him as a hero of republican resistance. Neither view captures the full story.

The historical Brutus was a man who faced an impossible situation and chose badly. He killed for an ideal that was already dead. The Roman Republic had been failing for decades before Caesar. The political system couldn't handle the strains of empire: the loyal armies, the ambitious generals, the wealth inequality, the breakdown of traditional restraints. Caesar was a symptom, not the disease. Killing him just made the collapse messier.

Brutus's final words about "wretched virtue" capture the tragedy. He worshipped an idea of the Republic that probably never existed as he imagined it. He sacrificed everything, including a man who loved him, for an abstraction. At the end, he realized that in politics, principles without power are just rhetoric.

His ancestor had built a Republic on the graves of his sons. Marcus Brutus buried that Republic while trying to save it. Five centuries of Roman self-governance ended on a battlefield in Macedonia, with a philosopher falling on his sword because the virtue he had worshipped turned out to be just a name.

Frequently Asked Questions

1Was Brutus actually Caesar's son?

Probably not. Caesar had an affair with Brutus's mother Servilia, but Brutus was born when Caesar was about fifteen years old. The timing doesn't work. What is certain is that Caesar treated Brutus like a son and seemed genuinely hurt by the betrayal.

2What were Caesar's actual last words?

Ancient sources disagree. Some say he spoke in Greek: 'Kai su, teknon?' (You too, my child?). Others say he said nothing at all. Shakespeare's 'Et tu, Brute?' is a later invention. What all sources agree on is that Caesar stopped fighting when he recognized Brutus.

3Why did the assassination fail?

The conspirators had no plan for what would happen after Caesar died. They assumed Rome would spontaneously restore republican government, but the power structures that enabled Caesar, including his loyal armies and political networks, remained intact. Octavian and Antony simply took control of them.

4How did Cassius die?

Cassius killed himself after the first battle of Philippi because he thought his side was losing. They were actually winning. He couldn't see clearly through the dust and confusion. It's one of history's most pointlessly tragic deaths.

5What happened to the other conspirators?

Most of the sixty conspirators died within three years. Some were killed in the proscriptions, some died at Philippi, some committed suicide. None of them saw the Republic restored.

Experience the Full Story

Follow the final days of the Roman Republic, from Caesar's assassination to the tragedy at Philippi, narrated by Lumo, an ancient witness to Rome's transformation from Republic to Empire.

Hear Their Story

Related Articles

Experience Marcus Junius Brutus's Story

Go beyond the biography. Hear Marcus Junius Brutus's story told by Lumo, your immortal wolf guide who witnessed these events firsthand.