The Death Lists

After Julius Caesar fell on the Ides of March, his killers expected gratitude. They got silence. Rome locked its doors. The liberators, as they called themselves, discovered that assassinating a dictator and restoring a republic are not the same thing.

The men who seized power next had no interest in restoration. Octavian, Caesar's adopted heir, was eighteen years old when he learned his name was now worth killing for. Mark Antony, Caesar's loyal general, controlled the legions. A third man, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, commanded enough soldiers to matter.

In November 43 BCE, these three met on a small island in a river near Bologna. They carved up the Roman world among themselves and gave their arrangement a name: the Second Triumvirate. Unlike Caesar's earlier coalition with Pompey and Crassus, this one had legal force. The Senate, cowed and desperate, granted them official power to reform the state.

The first reform was murder.

Proscriptions: Legalized Killing

The triumvirs published lists. Names on papyrus, posted in public squares across Rome. If you saw your name, you were already legally dead. Anyone could kill you for a reward. Your property was seized. Your family was ruined.

The proscriptions of 43 BCE killed around 300 senators and 2,000 equestrians. Some died for their politics. Many died because they owned land someone wanted. Sons denounced fathers. Slaves betrayed masters. The informant's reward was a portion of the condemned man's estate.

This was not new. The dictator Sulla had invented proscriptions forty years earlier. But Sulla had used them against his political enemies. The triumvirs used them for profit. They needed money to pay their armies. Dead men's estates provided it.

The most famous name on the list was Marcus Tullius Cicero.

The Death of Cicero

Cicero was sixty-three years old and had been Rome's most celebrated orator for four decades. He had exposed the Catiline conspiracy. He had saved the Republic with a speech and never stopped reminding everyone about it. He had mocked Mark Antony in a series of devastating orations called the Philippics, comparing him to every tyrant in history.

Antony wanted his head. Literally.

Cicero tried to flee. His slaves carried him in a litter toward the coast, toward a ship that might have taken him to safety. He almost made it.

The soldiers caught him on December 7, 43 BCE, on a road near his villa at Formiae. Cicero ordered his bearers to stop. He looked at the centurion, Herennius, and offered his neck.

They cut off his head and his hands. The hands that had written the Philippics. The head that had spoken them.

Antony's wife Fulvia, according to ancient sources, took Cicero's head and stabbed the tongue with her hairpin. Revenge for all those words.

This is what Rome had become. The men who killed Caesar to save the Republic had unleashed something worse than any dictator.

The Liberators Flee East

While Rome drowned in blood, Marcus Brutus and Gaius Cassius fled to the eastern provinces. They still called themselves liberators. They still believed they had saved something.

Caesar had assigned Brutus to Macedonia and Cassius to Syria before the assassination. After the Ides of March, the Senate tried to sideline them with minor provinces, but both men ignored the reassignment. Brutus went to Macedonia. Cassius went to Syria. They were supposed to govern these territories for Rome. Instead, they prepared for war.

Cassius proved better at this than anyone expected. He stripped the eastern provinces of men and treasure. He defeated a Dolabella force that challenged him. By mid-42 BCE, he commanded a substantial army and had accumulated enough gold to pay it.

Brutus consolidated control over Macedonia and Greece. He was less ruthless than Cassius but equally effective. Together, they gathered nineteen legions and thousands of auxiliary cavalry. Nearly 100,000 men.

Their camp became a gathering place for everyone who had sided against Caesar and survived. Former Pompeians. Senators who had fled the proscriptions. Young nobles whose fathers had died in earlier civil wars. They called their cause the Republic. They believed in it enough to die.

The Second Triumvirate Prepares

Octavian and Antony crossed the Adriatic in late summer of 42 BCE with everything they had. Approximately twenty-one legions. Over 100,000 soldiers. Lepidus stayed behind to govern Rome and Italy.

The journey was difficult. Republican sympathizers still controlled the seas. Some of their supply ships were lost to storms. Disease spread through the camps. Octavian himself fell ill and had to be carried in a litter.

Antony took command of the active forces. He was the better general and everyone knew it. Octavian was useful for his name and his connection to Caesar's divine legacy, but in battle, Antony gave the orders.

They found Brutus and Cassius waiting near the town of Philippi, in eastern Macedonia. The liberators had chosen their ground carefully.

The Battlefield

Philippi sits on a plain between two mountain ranges, near the northern coast of the Aegean Sea. The Via Egnatia, the main road connecting Rome's eastern empire, passed directly through it.

Brutus and Cassius positioned their camps on rising ground south of the road. Marshes protected their northern flank. Mountains guarded the south. They had fortified the gap between the camps with trenches and palisades. Their supply lines ran to the port of Neapolis, where their fleet controlled the sea.

Antony and Octavian arrived to find the position almost impossible to assault. A frontal attack would be suicide. But they had a problem: their supply situation was far worse than the enemy's. Time favored Brutus and Cassius.

The republican strategy was simple. Wait. Let Antony's army starve. Refuse battle. Win without fighting.

It almost worked.

The First Battle: October 3, 42 BCE

Antony forced the issue. He led his men into the marshes north of the battlefield, building causeways through the wetlands to outflank the republican position. Dangerous work, hidden from the main camps by reeds and muddy ground.

Cassius discovered the operation and built counter-fortifications to block it. The marshes became a maze of earthworks and trenches, two armies probing at each other through the fog and the wet.

On October 3, Antony attacked. He committed his forces against Cassius's fortifications in the marsh while the main armies watched from the plain.

Then everything collapsed into chaos.

Brutus's soldiers, stationed on the republican left, saw fighting to their south and charged without orders. They slammed into Octavian's lines before Octavian was ready. The attack was devastating. Brutus's legions swept through Octavian's camp, killed thousands, and nearly captured Octavian himself.

Octavian was not in his tent. Ancient sources claim he had dreamed of danger and moved to a different location. More likely, he was simply away from the fighting because of his continuing illness. Either way, the assassins missed their chance to kill Caesar's heir.

But while Brutus was winning on one flank, Cassius was losing on the other. Antony's troops broke through his lines and stormed his camp. Cassius retreated to high ground as his position crumbled.

He sent a scout to find out what had happened to Brutus. The scout returned with confused reports. Cassius saw cavalry approaching through the dust. He couldn't tell if they were friend or enemy.

In fact, they were Brutus's men, sent to report victory.

The Suicide of Cassius

Gaius Cassius Longinus was a practical man. He had organized the conspiracy against Caesar. He had argued for killing Mark Antony alongside the dictator. Brutus's idealism had overruled him.

Now, on the ridge above his burning camp, he made a practical decision. If the battle was lost, there was no point in being captured. He ordered his freedman Pindarus to kill him. One thrust. Quick.

The cavalry that had alarmed him rode closer. When they reached Cassius's body, they were wearing Brutus's colors. They had come to tell him they had won.

The first Battle of Philippi was a draw. Each side had lost a camp. Each side had inflicted roughly equal casualties. But Cassius was dead, and the republican army had lost its best general.

Brutus buried him quietly. There was no time for proper mourning.

The Waiting Game

For three weeks, nothing happened. Brutus consolidated command of the combined republican army. Antony repaired his positions and waited for supplies.

The strategic situation still favored the republicans. Their fleet intercepted two triumvirate legions being shipped as reinforcements, destroying both transport squadrons. Brutus's supply lines remained secure. Time was still on his side.

But the army knew Cassius was dead. The soldiers knew their best commander had fallen on his own sword over a misunderstanding. Morale crumbled. Officers began defecting to the other side.

Brutus understood war well enough. He had governed Cisalpine Gaul for Caesar and served in the civil war against Pompey. He knew the mathematics of supply and attrition. He knew that waiting was the right strategy.

He also knew his army was falling apart.

The legions demanded battle. Republican soldiers wanted revenge for Cassius. They wanted to finish what they had started. They shouted for their commander to lead them forward.

Brutus, the philosopher, the idealist, the man who had killed his mentor for principle, gave in.

The Second Battle: October 23, 42 BCE

The second Battle of Philippi was decisive.

Brutus led his forces down from the heights in the afternoon of October 23. The armies met on the plain between the camps. This time there was no confusion, no separate actions on different flanks. It was a straight fight, legion against legion.

For a time, the line held. Roman soldiers on both sides fought with the desperation of men who knew only one army would walk off this field. Shield walls crashed together. Centurions died trying to push forward. Bodies piled in the gaps between formations.

Then the republican line cracked.

Plutarch records that Brutus's cavalry broke first. Once the flanks collapsed, the center could not hold. Soldiers began running. The retreat became a rout.

Brutus escaped with a handful of loyal followers. They made for the hills north of the battlefield as darkness fell.

The Death of Brutus

That night, Brutus gathered what remained of his command staff. A few loyal officers. A handful of friends. The Republic they had killed for was dead, and they all knew it.

According to Cassius Dio, Brutus quoted a line from Greek tragedy, attributed to Hercules in a lost play: "O wretched virtue, you were but a name, and I worshipped you as real, but you were the slave of fortune."

He had spent his life believing that virtue mattered. That principle was worth more than power. That the Republic was an ideal worth dying for. Now, at the end, he wondered if any of it had been real.

He ran onto his sword. Some ancient sources say his friend Strato held the blade for him. Others say Brutus positioned the weapon and threw himself forward. The details vary. The result does not.

Marcus Junius Brutus died believing he had failed. He was right. He had killed the man who loved him, started a civil war, and achieved nothing except seventeen more years of bloodshed.

But he died with philosophical consistency. He had lived for an idea. He died when that idea proved empty.

Mark Antony's Tribute

When Mark Antony found Brutus's body the next morning, he did something unexpected. He removed his own purple cloak, the mark of a Roman general, and covered the corpse with it.

According to Plutarch, Antony called Brutus the only one of Caesar's assassins who had acted from genuine conviction rather than personal hatred or ambition. The others had stabbed Caesar for jealousy, for revenge, for fear. Brutus had believed he was saving the Republic.

Antony ordered Brutus's body cremated with full honors. The ashes were sent to Servilia, Brutus's mother and Caesar's longtime lover. The woman had lost both the men she loved to the same terrible history.

The Aftermath

The Battle of Philippi destroyed the republican cause. The surviving conspirators scattered. Some were hunted down in the following months. Others died in obscure skirmishes or took their own lives. Within three years of the Ides of March, almost everyone who had stabbed Caesar was dead.

The victors divided the Roman world. Antony took the wealthy eastern provinces and eventual alliance with Cleopatra in Egypt. Octavian took Italy and the west, along with the task of settling the veterans who had won the war.

Lepidus received Africa and soon faded into irrelevance. By 36 BCE, Octavian had stripped him of power entirely.

The alliance between Antony and Octavian lasted longer than anyone expected. They hated each other, but they needed each other. That calculus changed slowly, then suddenly.

In 31 BCE, Octavian's forces defeated Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium. The lovers fled to Alexandria, where they both committed suicide in 30 BCE.

Octavian returned to Rome as the last man standing.

The Republic Becomes the Empire

The Senate voted Octavian a new name: Augustus. The Revered One. He accepted it with appropriate modesty.

He claimed to be restoring the Republic. He used republican forms, republican language, republican institutions. He called himself First Citizen rather than king. He let the Senate meet and deliberate, even if its decisions were increasingly irrelevant.

It was a polite fiction. Augustus held all real power. He controlled the legions. He decided peace and war. He appointed governors and approved candidates for office.

The Republic that Brutus killed Caesar to save had been dead for years before the Ides of March. Caesar had just stopped pretending. Now Augustus created a new pretense, and Rome accepted it because Rome was exhausted.

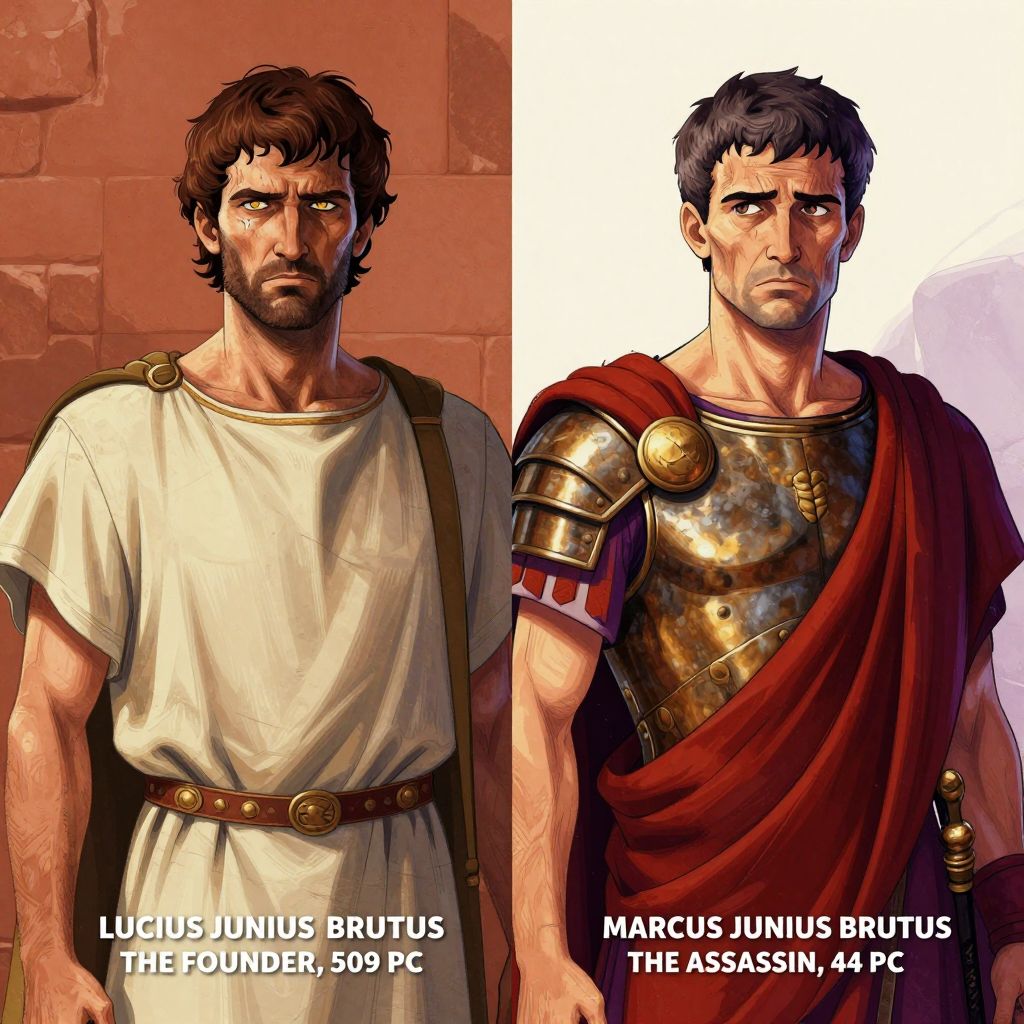

Two Men Named Brutus

Nearly five centuries separated two men with the same name and the same impossible burden.

Lucius Junius Brutus had founded the Roman Republic in 509 BCE. When his own sons conspired to restore the monarchy, he sentenced them to death. He watched them executed. He did not look away.

He understood what sacrifice meant. He paid the price in his own blood.

Marcus Junius Brutus claimed descent from that legendary founder. He killed the man who had treated him like a son. He believed the act would restore everything his ancestor had built.

The first Brutus executed his sons knowing exactly what it would cost. The second Brutus killed his father-figure and expected applause.

One built a republic on sacrifice. The other destroyed it with a murder he called liberation.

Why Philippi Matters

The Battle of Philippi marked the end of the Roman Republic as a functioning political system. The institutions survived for centuries as decorative fixtures of imperial power. The Senate met. Elections happened. Consuls took office.

But after Philippi, no one seriously believed the old order could return. The men who had staked everything on republican restoration were dead or scattered. Their cause had become a corpse on a Macedonian battlefield.

What replaced it was arguably more stable. The civil wars that had torn Rome apart for generations finally ended when Augustus accumulated enough power to prevent them. The Pax Romana that followed brought two centuries of relative peace to the Mediterranean world.

But something was lost that could not be recovered. The ideal that no man should hold permanent power over Rome. The principle that citizenship meant self-governance. The belief that virtue and the republic were the same thing.

Brutus died thinking virtue was just a word. Maybe he was right. Maybe the Republic had always been an oligarchy with good marketing. Maybe the ideals he killed for had never described anything real.

Or maybe the ideals were real and the men were not good enough to live up to them.

Either way, the question died with him. After Philippi, there would be emperors.

Frequently Asked Questions

1How many battles were fought at Philippi?

Two battles were fought at Philippi, separated by three weeks. The first on October 3, 42 BCE was a draw, though Cassius committed suicide believing he had lost. The second on October 23 was a decisive victory for Octavian and Mark Antony, ending the republican cause.

2Why did Cassius kill himself?

Cassius killed himself over a tragic misunderstanding. During the first battle, his camp was overrun while Brutus was winning on another part of the field. Cassius saw cavalry approaching through the dust and could not tell if they were friend or enemy. He ordered his freedman to kill him before they arrived. The riders were actually Brutus's men coming to report victory.

3What did Brutus say before he died?

According to Cassius Dio, Brutus quoted a line from a lost Greek tragedy: 'O wretched virtue, you were but a name, and I worshipped you as real, but you were the slave of fortune.' He had spent his life believing virtue and principle mattered above all else, and at the end he questioned whether any of it had been real.

4What happened to the assassins of Caesar?

Almost all of Caesar's assassins were dead within three years of the Ides of March. Brutus and Cassius died at Philippi. Others were hunted down by Octavian's agents, killed in minor battles, or took their own lives. The proscriptions killed many former conspirators before Philippi. By 40 BCE, the liberators were effectively extinct.

5How did Mark Antony honor Brutus after his death?

Antony covered Brutus's body with his own purple general's cloak and called him the only conspirator who had acted from genuine conviction rather than hatred or ambition. He ordered the body cremated with full honors and sent the ashes to Brutus's mother Servilia.

Experience the Fall of the Republic

From Caesar's assassination to Brutus's final words, hear the end of the Roman Republic told by an ancient witness.

Listen to Related Stories

Key Figures

Listen to the Full Story

Experience history through immersive audio lessons narrated by Lumo, your immortal wolf guide.