The Monarchy Rome Hated

By 509 BCE, Romans were done with kings. The Tarquin dynasty had ruled for over a century, and with each generation, the hatred grew deeper. Tarquinius Superbus ("Tarquin the Proud") had seized power through assassination, murdering his own father-in-law King Servius Tullius to take the throne. He murdered senators who opposed him, confiscated property from wealthy families without trial, and ruled Rome not as a king but as a despot.

The Senate, once Rome's deliberative body, had been reduced to a rubber stamp. Noble families watched their power erode. The people watched taxes climb while the king built monuments to himself. Tarquinius didn't even pretend to care what Romans thought. The name "Superbus" wasn't just about pride. It was contempt.

But here's the problem with overthrowing kings: you need a reason the people can't ignore. Grumbling about taxes won't start a revolution. You need something that strikes at the heart of Roman values. Virtue. Honor. The sanctity of the family.

The Tarquins were about to give Rome that reason. And a woman named Lucretia was going to make sure they couldn't take it back.

The Setup

The story begins with a stupid bet. During the siege of Ardea, a group of young Roman nobles were drinking in camp, arguing about whose wife was most virtuous. Collatinus, a cousin of the king, bragged that his wife Lucretia was so devoted she stayed home spinning wool while other noblewomen went out drinking.

"Prove it," said Sextus Tarquinius, the king's son.

So they rode back to Rome in the middle of the night to check. They found the other wives at parties. But when they arrived at Collatinus's house in Collatia, there was Lucretia, sitting by lamplight, working her loom, exactly as her husband had described.

Sextus saw her and wanted her. Not because she was beautiful (though she was). Because she was virtuous. Because she belonged to someone else. Because taking her would violate everything Rome claimed to stand for.

He came back a few nights later. Alone.

She Had a Plan

The next morning, Lucretia sent messengers to her father Spurius Lucretius and her husband Collatinus: "Come home immediately. Bring witnesses."

Not "come home, something terrible happened." Not "I need you." The message was specific, calculated. Bring witnesses.

The night before, Sextus Tarquinius (son of King Tarquinius Superbus) had forced himself on her at knifepoint in her own home. He'd threatened that if she resisted, he'd kill her and place a naked slave's body beside her, then tell everyone he'd caught them in adultery. The perfect threat: her death would look like justified punishment for betraying her husband, and no one would question a prince's word.

She didn't resist. She let him leave alive.

Because Lucretia had a plan. And it required witnesses.

The Testimony

When the men arrived (her husband Collatinus, her father Spurius Lucretius, trusted friends, and a man everyone thought was a harmless fool named Brutus), they found Lucretia dressed in black. Mourning clothes. Before anyone had died.

She was sitting upright, spine straight, hands folded. Too calm. This wasn't a woman broken by trauma. This was a woman who had made a decision and was ready to execute it.

Lucretia told them exactly what happened. Every detail. The assault. The knifepoint. The threat of murder and false accusation. She named Sextus Tarquinius specifically. The king's son. She made sure everyone in the room understood who had done this.

The men reacted with horror, with promises of justice, with assurances that she bore no guilt. Collatinus reached for her. "None of this was your fault. You're innocent. The crime is his alone."

But Lucretia wasn't looking for absolution. She was delivering testimony.

"My body is defiled. But my mind is innocent. It is only the body that has sinned, and for that, there must be payment."

The words sounded rehearsed. Because they were. She'd spent all night preparing them.

"I absolve myself of sin. But not of punishment. No woman will ever use Lucretia as an excuse to live in shame."

That last line wasn't for her husband or father. It was for every Roman woman who would hear this story for centuries to come. She was authoring her own legend.

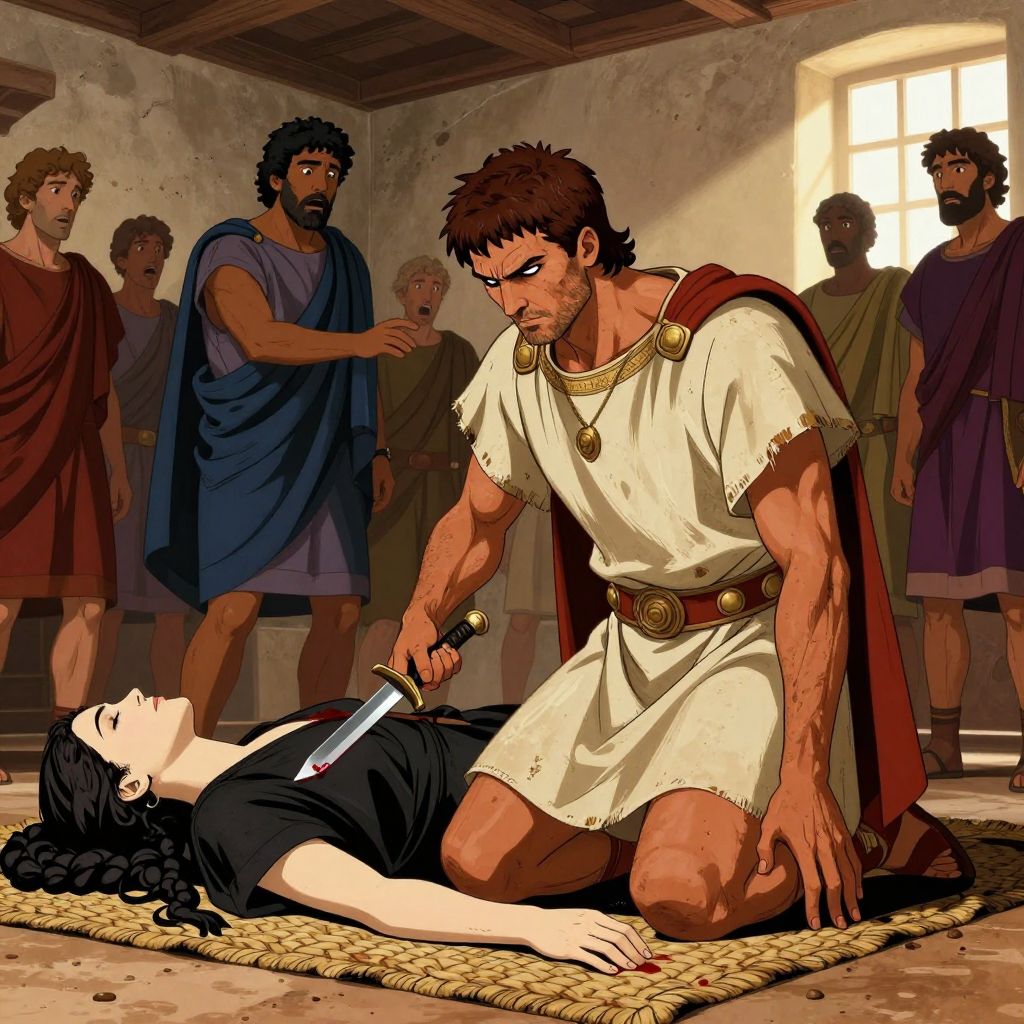

The Weapon

She pulled a knife from under her dress and drove it into her own heart.

The room erupted. Collatinus screamed. Her father collapsed.

Lucretia knew what she was doing. She'd named her attacker. She'd gathered witnesses. She'd given testimony that couldn't be denied or dismissed as rumor. And now she'd made herself a martyr, someone whose death demanded a response.

This wasn't a woman broken by shame. This was a political act disguised as suicide.

The Fool Drops His Mask

While everyone else wept, one man was already moving. Lucius Junius Brutus (the king's nephew everyone dismissed as an idiot, the fool who'd been brought along because nobody thought twice about bringing the fool) walked through the chaos, knelt beside Lucretia's body, and pulled the knife from her chest. Still wet with blood.

For twenty years, Brutus had played a role. His name literally meant "stupid." He'd adopted the persona after King Tarquinius murdered his father and brothers to seize their wealth. The fool act was survival: make yourself look harmless, and tyrants ignore you. While Rome's nobles bent the knee to Tarquinius, Brutus shuffled around in stained tunics, grinning vacantly, invisible.

Lucretia's death changed the equation. She'd created the opening. Now Brutus had to take it.

He stood, holding the bloody knife, and spoke. His voice was different. Not the simpering whine these men had heard for two decades. Cold. Level. The voice of someone who'd been waiting for this moment since childhood, rehearsing it in his mind every day for twenty years.

"By this blood (most pure before the outrage of a prince) I swear, and you as my witnesses, that I will drive out Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, his wife, his children, and all his cursed house. Rome will never have another king."

The room went silent. The men stared. This wasn't the Brutus they knew. This was a strategist. A commander. Someone who'd been hiding in plain sight.

Collatinus was the first to understand. His wife had just weaponized her death, and Brutus (the fool, the coward, the joke) was going to use it to tear down the monarchy. One by one, the men knelt. Not just in grief.

In fear.

They realized they'd been sharing wine with a predator for two decades.

The Revolution Spreads Like Fire

The knife was still wet when they started organizing. Brutus didn't waste time on grief. He took Lucretia's body to the Roman Forum, displayed it publicly, and told the story to anyone who would listen. This is what the king's son did. This is what the Tarquins think of Roman virtue. This is what happens when tyrants rule unchecked.

The reaction was explosive. Romans poured into the Forum. The story spread through every neighborhood, every tavern, every household. Sextus Tarquinius (the king's own son) had raped a noblewoman in her own home. And Lucretia, rather than live with the shame, had killed herself after naming her attacker in front of witnesses.

It was the perfect catalyst. Romans had tolerated Tarquinius Superbus's tyranny because revolution is dangerous and failure means death. But Lucretia gave them a grievance that couldn't be ignored, a martyr whose death demanded response. Brutus made sure they understood: this wasn't just about one woman. This was about what kind of city Rome would be.

Within days, Brutus had the city in open revolt. The army, besieging Ardea under the king's command, defected when they heard the news. Soldiers who'd fought for Tarquinius marched back to Rome and joined the revolutionaries. The king's garrison in the city surrendered without a fight.

Tarquinius Superbus (the last king of Rome) fled the city he'd ruled as a tyrant. His wife, his sons, his entire household went with him. The gates of Rome closed behind them. According to tradition, they were permanently banished. The Tarquin family would never set foot in Rome again.

Building the Republic

In the monarchy's place, Rome created something new. Not another king. Not a dictatorship with a different name. A Republic, from res publica, "the public thing." Power would belong to the people, exercised through elected representatives.

The Romans designed the system to prevent another Tarquinius. Two elected consuls instead of one king, each with veto power over the other. Term limits: one year, then you're out. A Senate with real authority, not a rubber stamp. Checks and balances at every level. If one consul tried to become a tyrant, the other could stop him. If both consuls colluded, the Senate could intervene.

The first two consuls elected? Lucius Junius Brutus (the fool who'd hidden in plain sight for twenty years) and Collatinus, Lucretia's widowed husband. The revolutionary and the martyr's family, ruling together.

But there's a darker epilogue to Collatinus's story. Within months, Romans decided that even having the name "Tarquinius" in the government was too much. Collatinus's full name was Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus. He was related to the royal family by blood, a cousin of the king. Brutus, his co-consul and supposed friend, asked him to voluntarily resign and go into exile.

Collatinus went. He'd already lost his wife to the revolution. Now he lost his city too.

The Legacy

Rome wouldn't have another king for nearly 500 years. The Republic became Rome's identity, the foundation of everything that followed. When Julius Caesar got too close to kingship in 44 BCE, the conspirators who murdered him included a man named Marcus Junius Brutus, who claimed descent from Lucius Junius Brutus, the founder of Roman liberty.

The story of Lucretia became foundational to Roman culture. Poets retold it. Historians recorded it. Parents taught it to their children as a lesson in virtue and sacrifice. For Romans, Lucretia was everything their Republic stood for: personal honor, rejection of tyranny, the willingness to sacrifice for the greater good.

But modern interpretations are more complicated.

How Romans Remembered Her

For Romans, Lucretia was a hero. She was virtue (pudicitia), the willingness to die rather than live with dishonor. Roman women were taught to emulate her. Statues depicted her. Historians like Livy told her story as a foundational myth of the Republic, the moment Rome rejected tyranny.

But there's a dark edge to how Romans idealized her. They praised her for killing herself. They made her suicide the proof of her innocence. The implicit message: a truly virtuous woman wouldn't want to live after being raped, even if the rape wasn't her fault. Survival meant shame. Death meant honor.

That's the version Romans passed down for centuries. Lucretia the martyr. Lucretia the symbol of virtue. Lucretia who chose death over dishonor.

Modern Readings

Modern readers see something different. Yes, Lucretia died. But before she died, she summoned witnesses. She gave detailed testimony. She named her attacker (the king's son) in front of people who could spread the story. She staged her death for maximum political impact.

This wasn't a woman destroyed by shame. This was a woman who saw an opportunity and took it. She understood that the Tarquins had given Rome's revolutionaries exactly what they needed: a martyr whose death could justify regime change. So she made herself that martyr.

Was it calculated? Absolutely. The mourning clothes before anyone died. The witnesses. The rehearsed speech. The knife hidden in her dress. Lucretia spent the night after the assault planning her own death for maximum political effect.

Was it tragic? Also yes. She lived in a culture that valued female virtue above female life. A culture where being raped (even at knifepoint, even by a prince) meant permanent dishonor. She saw no future for herself after what Sextus did. So she turned her death into a weapon.

Why This Matters

Lucretia's story gets told as a tragedy, but that framing misses the calculated genius of what she did. She didn't just die. She weaponized her own martyrdom. She turned a sexual assault into a political crisis that tyrants couldn't survive.

She summoned witnesses before dying so her testimony couldn't be dismissed as gossip. She named Sextus Tarquinius in front of his cousin and other nobles, making it impossible to cover up or deny. She killed herself in front of men who could spread the story, knowing Romans would demand justice for her death in a way they'd never demand justice for her survival.

The centuries of the Roman Republic (its expansion, its conquests, its eventual transformation into an empire) all trace back to this moment. When a Roman noblewoman refused to let her assault be swept under the rug. When a fool named Brutus dropped his mask and picked up a knife. When Rome's hatred of kings finally found a cause worth dying for.

Whether you see Lucretia as a tragic victim or a cold-eyed revolutionary probably says something about how you read history. Maybe she was both. Maybe that's the point.

Frequently Asked Questions

1Is the story of Lucretia historically accurate?

The story was recorded by Roman historians like Livy, but it's probably more legend than literal history. The Roman monarchy definitely ended around 509 BCE, and the Romans themselves traced the Republic's founding to this story. Whether Lucretia was a real person or a symbolic figure remains debated.

2Why did Lucretia kill herself?

According to the Roman account, Lucretia killed herself to prevent other women from using her survival as an excuse to 'live in shame.' But the story also frames her death as a deliberate act to force political action. She gathered witnesses, gave testimony, and died in front of them, creating an undeniable martyr.

3Who was Brutus in Lucretia's story?

Lucius Junius Brutus was a nobleman who spent twenty years pretending to be mentally impaired after King Tarquinius killed his father and brothers. The name 'Brutus' actually means 'dull' or 'stupid.' He used Lucretia's death as the catalyst for revolution and became one of the first two consuls of the Roman Republic.

4What happened to Sextus Tarquinius?

Sextus fled Rome with his family during the revolution. According to tradition, he was later killed in battle or assassination. The entire Tarquin family was expelled from Rome and permanently banned from returning.

Hear the Full Story

Experience Lucretia's story as told by Lumo, including the years Brutus spent hiding behind his mask.

Listen to Related Stories

Key Figures

Listen to the Full Story

Experience history through immersive audio lessons narrated by Lumo, your immortal wolf guide.