The Property That Fought Back

Rome ran on slavery. Millions of people treated as tools with heartbeats. Farm workers. Household servants. Mine laborers. And at the bottom of that hierarchy, reserved for the most dangerous, the most expendable — gladiators.

Entertainment for the wealthy. Blood sport for the masses. Men trained to kill each other while Rome watched and cheered.

The gladiator schools were prisons disguised as training facilities. High walls. Armed guards. Locked barracks at night. You didn't graduate from gladiator school. You died there, or you got too old to fight and they killed you anyway.

The owners called it business. The gladiators called it what it was: a death sentence with extra steps.

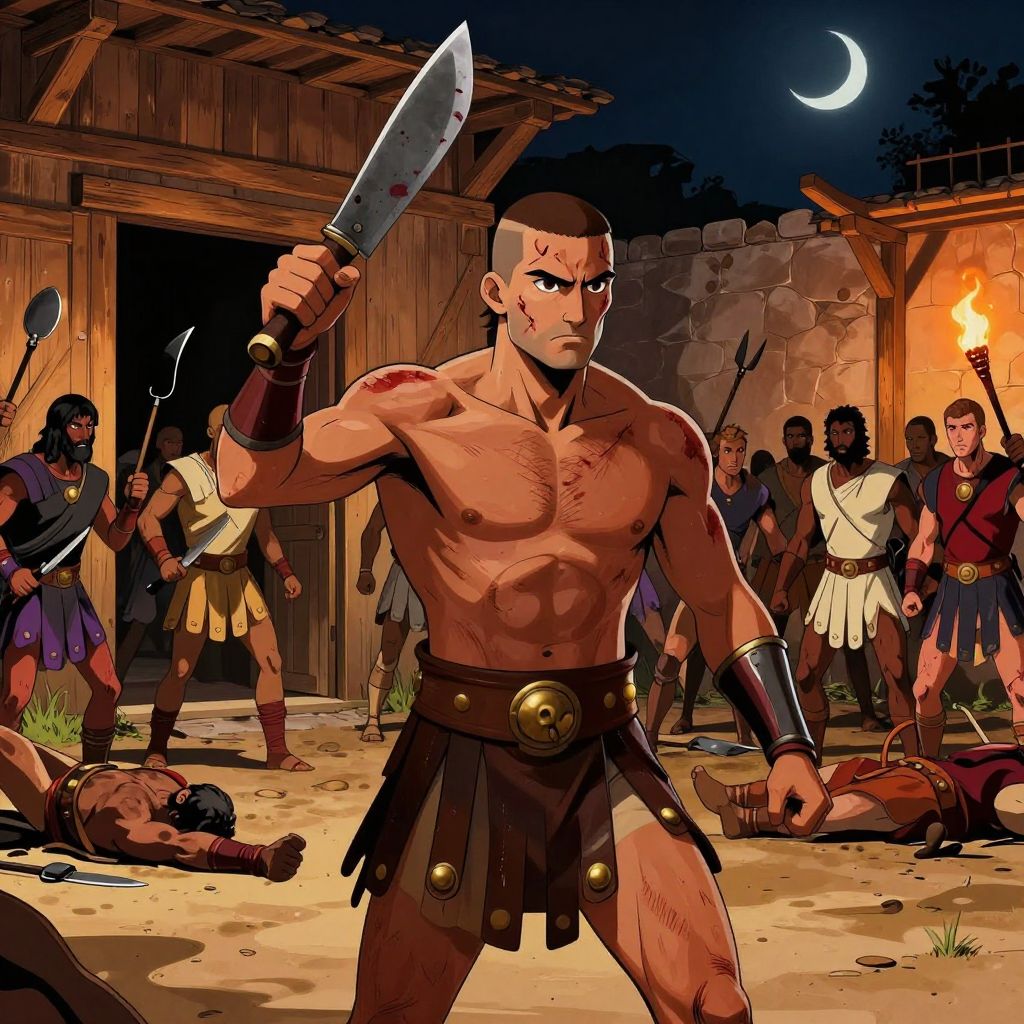

Seventy Men, Kitchen Knives

73 BCE. A gladiator named Spartacus escaped from a training school in Capua with seventy men. Armed with kitchen knives.

The plan was desperate. The execution was brutal. They overpowered the guards, broke into the kitchen, grabbed whatever they could use as weapons. Meat cleavers. Cooking spits. Iron hooks. Anything sharp.

Gladiators weren't soldiers. They were property. Locked in barracks, trained to kill each other for rich people's entertainment. Most never expected to leave alive.

Seventy of them with kitchen implements — choppers, spits, anything they could grab from the kitchen.

They shouldn't have lasted a week. They lasted two years.

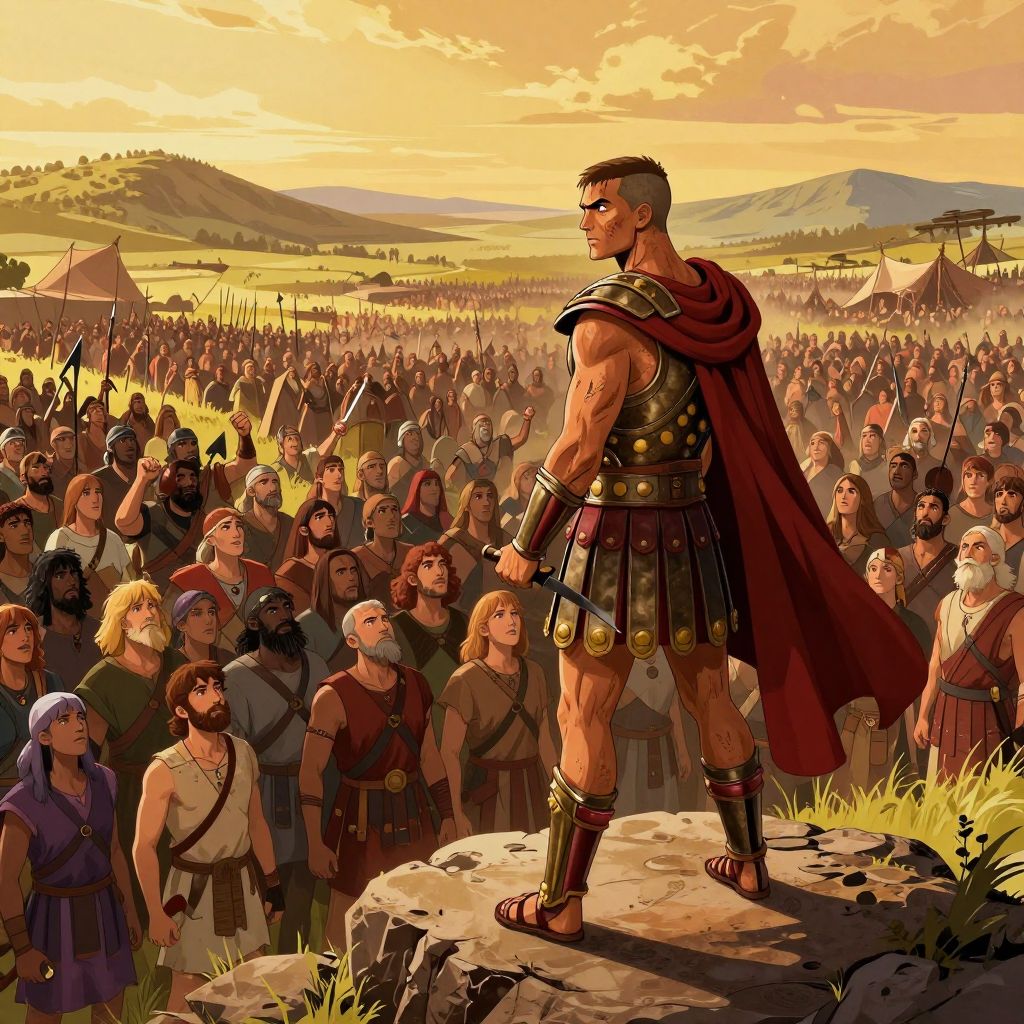

The Army That Shouldn't Exist

They seized a wagon of gladiator weapons on the road. Now they were actually armed.

The rebels made camp on Mount Vesuvius — the volcano that would later bury Pompeii. Rome sent Gaius Claudius Glaber with 3,000 militia to blockade the only path down. Standard operation. Starve them out, wait for surrender, crucify the survivors.

Spartacus found vines growing on the mountainside. His men wove them into ladders and climbed down the cliffs on the opposite side of the mountain. They attacked the Roman camp from behind while the militia was still watching the wrong path.

Glaber's force was annihilated. The rebels took their weapons, their armor, their supplies.

Rome sent a praetor to handle the problem. Spartacus destroyed him. They sent another. Destroyed. Every force Rome threw at them came back in pieces.

Each victory brought more recruits. Farm slaves. Mine workers. Household servants. The people Rome pretended didn't exist.

Seventy became seven hundred. Seven hundred became seven thousand. Seven thousand became seventy thousand.

An army of people Rome had written off as property.

This wasn't supposed to be possible. Slaves didn't form armies. They didn't defeat Roman commanders. They didn't march through Italy like they owned it.

But Spartacus wasn't just any slave. He was Thracian — from the warrior tribes beyond Rome's northern border. Before the arena, he'd been a soldier. Some sources say he'd served as an auxiliary in the Roman army itself before being enslaved, which would explain how he knew Roman tactics well enough to beat them. He knew how to fight. More importantly, he knew how to lead.

And every humiliation Rome suffered brought more people to his banner.

They marched north. Toward the Alps. Toward freedom.

The Choice

Spartacus could have walked out of Italy. He could have vanished into the wilderness beyond the mountains and never looked back.

He turned around.

Why?

Seventy thousand escaped slaves? Rome would never stop hunting them. There would be no peace. No safety. No freedom that lasted.

Better to die fighting than spend your life running.

The Man With Nothing to Lose

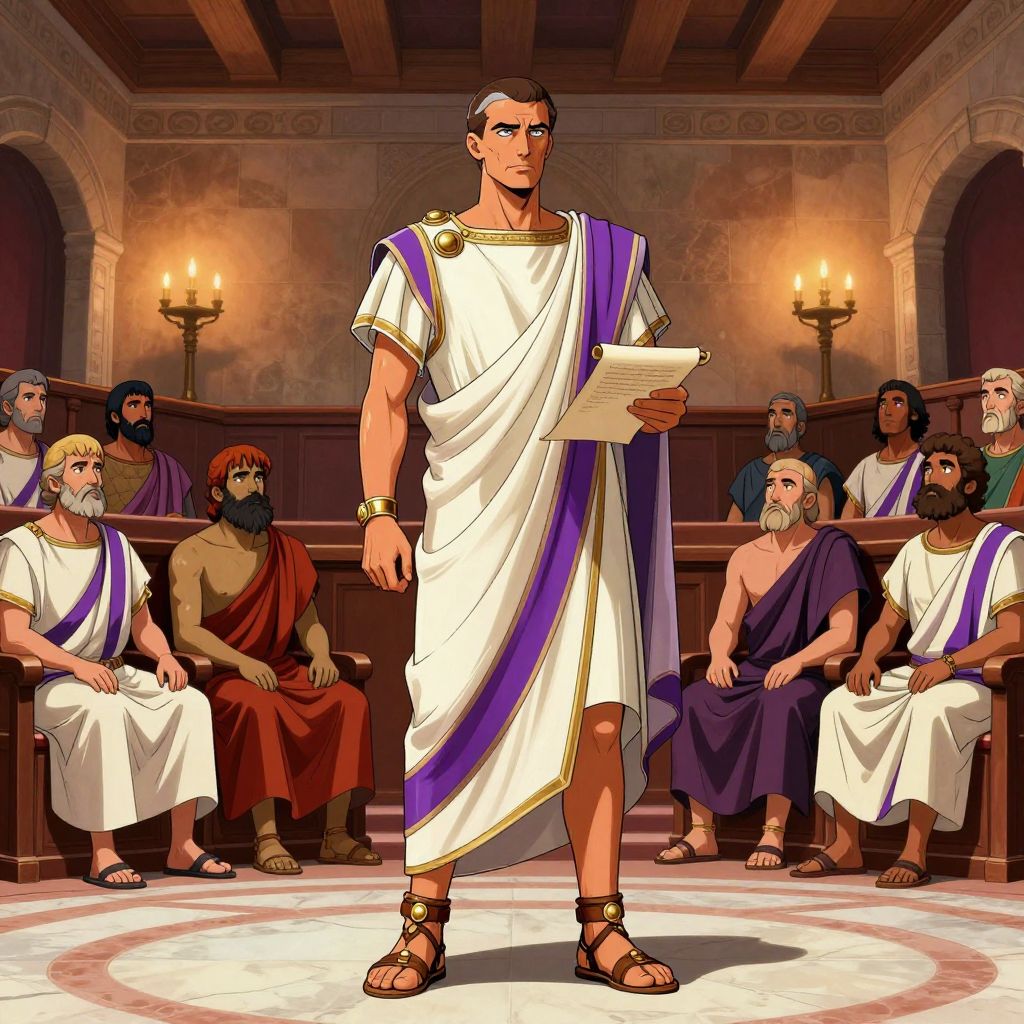

71 BCE. The Senate finally took it seriously. They gave the command to Marcus Crassus — the richest man in Rome.

Crassus had lost his father and brother during the purges of Marius and Cinna. He'd lost everything, fled to Spain, rebuilt his fortune from nothing. He knew what desperation looked like. He knew what people would do when they had nothing left to lose.

And he knew how to break them.

Other commanders had tried to defeat Spartacus with tactics and strategy. Crassus understood something simpler: you don't beat an army of the desperate by being merciful. You beat them by being more terrifying than anything they're running from.

Decimation

Crassus revived an ancient punishment that Rome had tried to forget.

When a unit ran from battle, you killed every tenth man. Not enemies. Your own soldiers. The lots were drawn. One in ten. Their own comrades beat them to death with clubs.

It's called decimation. From the Latin word for ten.

The soldiers who survived weren't grateful. They were traumatized. Broken. Remade into men who understood one simple truth: running from Spartacus might get you killed. Running from Crassus definitely would.

Crassus was teaching his army something simple: fear me more than you fear Spartacus.

It worked.

The Final Battle

The end came in 71 BCE. Spartacus had been pushed into the southern tip of Italy. Trapped between Crassus's legions and the sea.

Some say he tried to negotiate. Others say he knew negotiation was impossible. Rome didn't make deals with slaves.

He could have run. Could have tried to break through the lines, save himself and a handful of followers. Some of his lieutenants did exactly that.

Spartacus charged straight at the Roman center. Straight at Crassus himself.

He almost made it.

Spartacus died fighting. His body was never found. Some say his own men buried him in secret. Some say the Romans threw him in a mass grave, too mutilated to identify. Some say he made it out and lived his final days free, somewhere Rome would never find him.

But six thousand of his followers were captured alive.

The Forest of the Dead

Crassus crucified them along the Appian Way — Rome's main road south. A hundred and twenty miles of crosses. From Rome all the way to Capua, where it started.

Every hundred feet, another cross. Six thousand men dying slowly in the Mediterranean sun. Some lasted days. The strong ones, the unlucky ones, lasted a week.

The bodies were left to rot. A warning. For years, every Roman who traveled south passed through that forest of the dead. Merchants. Senators. Farmers taking grain to market. Children.

Everyone saw what happened when you defied Rome.

The message was clear: This is what freedom costs.

What Rome Learned

The rebellion taught Rome a lesson. Not the lesson Spartacus hoped for.

It didn't teach them that slaves were people. It didn't teach them that oppression creates resistance. It didn't teach them mercy.

It taught them that fear works. Brutal, public, unavoidable fear.

For generations after, when slaves whispered about rebellion, someone would mention the Appian Way. The conversation would end there.

Spartacus wanted to break the system. Instead, he showed Rome how to make it unbreakable.

The Death of the Republic

The Gracchi brothers tried to fix the system. Rome killed them.

Marius tried to save it. He drowned it in blood.

Sulla tried to reform it. He posted death lists.

Spartacus tried to break it. Six thousand of his followers hung on crosses as a warning.

Violence wasn't a tool anymore. It was the only language Rome spoke. That's what violence does. It doesn't just kill people. It kills the part of you that cares.

Crassus got his ovation — a lesser honor than a triumph, because Rome didn't consider a slave war worthy of one. Pompey stole some of the glory. Together with Caesar, they would form the First Triumvirate — three men dividing Rome between them like spoils of war.

Crassus with his money. Pompey with his army. Caesar with his ambition.

The Republic wasn't dying. It was already dead. They were just fighting over what was left.

Legacy

Spartacus failed. His rebellion was crushed. His followers were executed. His body disappeared into history.

His name didn't.

Marx wrote about him. The German communist Spartacus League took his name. Stanley Kubrick made a movie. Two thousand years later, people still remember the gladiator who made Rome afraid.

Not because he won. He didn't. But because for two years, seventy men with kitchen knives grew into an army that made the most powerful state in the Mediterranean scramble for solutions.

Rome crucified six thousand people to make sure nobody tried it again. They wouldn't have bothered if it hadn't scared them.

Frequently Asked Questions

1How many gladiators originally escaped with Spartacus?

About 70 gladiators escaped from the gladiator school in Capua in 73 BCE. They were armed only with kitchen implements — meat cleavers, cooking spits, and knives — until they seized a weapons transport wagon. Within two years, their numbers would grow to 70,000.

2Why did Spartacus turn back at the Alps?

Spartacus led his army to the Alps, where freedom lay beyond the mountains. But he turned back into Italy. The likely reason: 70,000 escaped slaves would be hunted forever. There would be no peace, no safety. He chose to fight Rome rather than spend his life running. It was a decision that would cost him everything.

3What is decimation?

Decimation was an ancient Roman military punishment that Crassus revived to discipline his troops. When a unit ran from battle, one in every ten soldiers was selected by lot and beaten to death by their own comrades with clubs. The word 'decimate' comes from this practice — it literally means 'to reduce by one-tenth.' Crassus used it to ensure his soldiers feared him more than they feared Spartacus.

4How many rebels were crucified after the rebellion?

About 6,000 captured rebels were crucified along the Appian Way, the main road from Rome to Capua. The crosses stretched for approximately 120 miles, with one every hundred feet. The bodies were left to rot as a warning and remained visible for years. Every traveler on Rome's busiest road had to pass through this forest of the dead.

5What happened to Spartacus's body?

Spartacus died in the final battle in 71 BCE, but his body was never found. Some historians believe his own men buried him in secret to prevent desecration. Others think he was thrown in a mass grave, too mutilated to identify. There are even legends that he escaped and lived his final days free, somewhere Rome would never find him.

6Who was Marcus Crassus?

Marcus Crassus was the richest man in Rome and the general who finally defeated Spartacus. He'd lost his father and brother during the purges of Marius and Cinna, and rebuilt his fortune from nothing. He understood that defeating desperate men required being more terrifying than anything they were running from. His victory over Spartacus launched his political career, eventually leading to the First Triumvirate with Pompey and Julius Caesar.

Experience the Full Story

From the escape with kitchen knives to the final battle, hear Spartacus's rebellion told by an ancient witness.

Listen to Related Stories

Key Figures

Listen to the Full Story

Experience history through immersive audio lessons narrated by Lumo, your immortal wolf guide.