The Man Who Fixed Everything

The Roman calendar was a disaster. Months drifted through seasons. February sometimes had twenty days, sometimes thirty. Politicians bribed priests to add extra days when they needed more time in office. By 46 BCE, the official calendar was three months ahead of the actual solar year. Winter festivals happened in autumn. Spring planting rituals occurred when crops were already rotting in the fields.

Julius Caesar fixed it in a year.

He brought in Sosigenes, an Alexandrian astronomer, and together they created a calendar based on the sun rather than the moon. Twelve months. 365 days. A leap year every four. The transition required adding ninety extra days to 46 BCE, making it the longest year in human history. Romans called it "the year of confusion."

But the confusion ended. The calendar worked. It worked so well that we still use it today, with only minor adjustments made in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII. Every time you check the date, you're using Caesar's system.

That was the infuriating thing about his dictatorship. He was genuinely good at it.

What "Dictator" Used to Mean

The Romans invented the dictatorship as an emergency measure. When the Republic faced existential threats, the Senate could appoint a single man with absolute power for up to six months. No debate. No vetoes. No appeals. One man to save the state.

The most famous example came in 458 BCE. The Aequi, a neighboring tribe, had surrounded a Roman army in the hills. The consuls were useless. The city panicked.

The Senate sent messengers to a farm outside Rome. They found an old farmer named Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, covered in dirt, pushing a wooden plow through his field.

"Rome needs you," they told him. "We're making you dictator."

He washed his hands. Put on a toga. Took command.

Sixteen days later, the war was over. Cincinnatus had taken command, marched out the legions, surrounded the Aequi who were surrounding the Romans, and forced their surrender. Total victory.

The Senate offered him everything. Land. Gold. Extended power. He was the most popular man in Rome. He could have had anything.

He refused. All of it. He walked back to his farm, picked up his plow, and kept working.

Someone asked him why he gave up power. His answer was practical, not philosophical: the crops would not plant themselves.

For four centuries, that was what "dictator" meant. Emergency power, briefly held, willingly surrendered. The office existed to save the Republic, not to replace it.

Then came Caesar.

The Dictatorship That Would Not End

Caesar crossed the Rubicon in January of 49 BCE. By the end of that year, he controlled Italy. By 48 BCE, he had crushed Pompey at Pharsalus and hunted down the remnants of the opposition across three continents.

The Senate kept extending his powers. First, he was dictator for a year. Then for ten years. Then, in 44 BCE, they made him dictator perpetuo. Dictator for life.

Cincinnatus held power for sixteen days. Caesar would hold it forever.

The Romans understood what this meant. Their entire political system was designed to prevent one-man rule. Two consuls so neither had supreme power. Term limits so no one stayed too long. Tribunes with veto power. The whole edifice of the Republic existed to distribute authority among many hands.

Caesar consolidated it in one.

The Reforms That Actually Worked

Here is what made Caesar dangerous: he used that power to fix things.

The calendar was just the beginning. Roman courts had become a farce, where wealthy defendants could delay trials indefinitely while poor plaintiffs died waiting for justice. Caesar streamlined the system, set time limits, and appointed judges who actually heard cases.

Citizenship had been a jealously guarded privilege. For centuries, Rome had conquered territory while treating the conquered as subjects rather than partners. Caesar extended citizenship to people in Cisalpine Gaul (modern northern Italy) and began granting it to communities in Spain and other provinces. Men whose grandparents had been enemies could now vote in Roman elections.

The grain dole, which distributed free food to urban poor, had ballooned out of control. Rather than eliminate it, Caesar reduced the rolls from 320,000 recipients to 150,000 through means testing, while simultaneously settling 80,000 citizens in new colonies abroad. He created jobs rather than just cutting welfare.

He rebuilt Carthage and Corinth, cities Rome had destroyed a century earlier. He planned a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth. He commissioned libraries, forums, and public buildings across the Roman world.

His land reform bills gave farms to veterans who had served in his legions. For Roman soldiers, this was revolutionary. Previous generals had promised land and failed to deliver. Caesar delivered.

The Enemies He Refused to Kill

The strangest aspect of Caesar's dictatorship was his clemency. Roman politics had been defined by proscriptions, death lists where winners executed losers and seized their property. Marius did it. Sulla did it on an industrial scale. Political victory meant political murder.

Caesar broke the pattern. He pardoned everyone.

Brutus had fought against him at Pharsalus. Pardoned. Cassius had served in Pompey's navy. Pardoned. Senators who had voted to declare him a public enemy were welcomed back. Officers who had commanded troops against his legions got new positions.

Some historians interpret this as arrogance. Caesar believed himself so powerful that defeated enemies posed no threat. Others see calculation. A living, grateful enemy was more useful than a dead one.

A third interpretation is simpler: Caesar was tired of killing Romans.

The civil war had lasted four years. He had fought Pompey's forces at Pharsalus, then his sons in Spain. He had besieged cities and burned camps and watched Romans slaughter each other across three continents. By 45 BCE, when the last opposition collapsed at Munda in Spain, Caesar had seen enough Roman blood.

Whatever his reasoning, the pardons created something dangerous. Sixty men who owed him their lives remained in Rome, watching him accumulate power, resenting the debt they could never repay.

The Crown He Almost Took

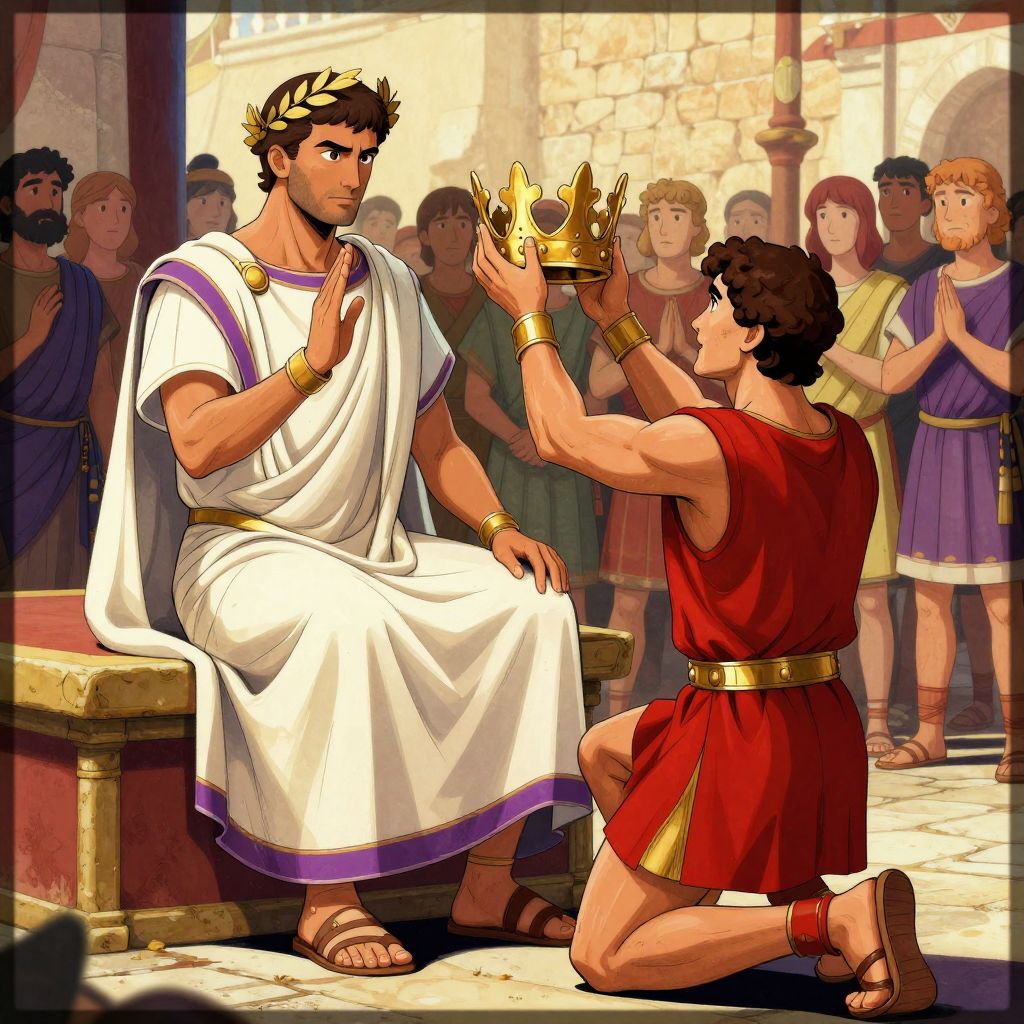

February 15, 44 BCE. The Lupercalia, one of Rome's oldest festivals. Young men ran through the streets nearly naked, striking women with leather straps. It was supposed to promote fertility, though by Caesar's time the religious meaning had faded into spectacle.

Caesar sat on a golden throne on the speakers' platform, dressed in the purple robes of his office. Mark Antony, his most loyal general, approached carrying a diadem, a golden band that signified kingship.

He offered it to Caesar. The crowd fell silent.

Caesar refused. The crowd cheered.

Antony offered it again. Caesar refused again. More cheering.

A third time. A third refusal. The crowd was ecstatic.

But watch the accounts carefully. Caesar did not simply reject the crown and move on. He had the moment recorded in the public records: on this date, Mark Antony offered Julius Caesar a crown, and Julius Caesar refused it.

Why record a refusal unless you wanted people to remember that the offer had been made?

Some ancient sources say Caesar was testing public opinion, measuring whether Rome was ready to accept a king. Others say Antony acted on his own, trying to see if the moment was right. A few suggest the whole thing was staged, a way to plant the idea while appearing to reject it.

Whatever the truth, the message was clear. Caesar had enough power to be offered a crown. The only thing preventing him from accepting was his own choice.

For men who believed in the Republic, that was not reassurance. It was a threat.

The Notes That Broke Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus was a philosopher. He wrote treatises on virtue. He believed in the Republic not as a system of government but as a moral ideal, the framework within which free men could pursue excellence.

He was also conflicted. Caesar had pardoned him after Pharsalus when he could have had him executed. Caesar treated him like a son. There were rumors, never confirmed, that Caesar was Brutus's biological father, given his affair with Brutus's mother Servilia.

But Brutus came from a particular lineage. His ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, had founded the Republic in 509 BCE by leading the revolt against the last king of Rome. When his own sons conspired to restore the monarchy, that first Brutus had condemned them to death and watched their execution without flinching.

The Junii were supposed to kill tyrants. It was in the blood.

Anonymous notes began appearing in early 44 BCE. On Brutus's praetor chair. On statues of his famous ancestor.

"You're sleeping, Brutus."

"Remember your ancestor."

"Are you really a Brutus?"

Brutus knew who was behind them. Gaius Cassius Longinus, a senator with a gift for conspiracy, was probing his conscience. But that did not make the messages less effective.

Brutus spent weeks in agony. He loved Caesar. He also believed that Caesar was destroying everything Rome was supposed to represent. The accumulation of offices. The lifetime appointment. The golden throne and purple robes. The crown offered at Lupercalia.

In the end, he convinced himself that murder was virtue. Killing Caesar would not be assassination but liberation. He was not betraying a father figure but saving the Republic.

He was wrong on both counts.

The Warning Caesar Ignored

A soothsayer named Spurinna had warned Caesar in early February: danger would last for thirty days, ending on the Ides of March. The Ides fell on the 15th in March, one of the calendar's fixed points that Romans used to mark time.

Caesar dismissed it. He dismissed most omens. He was 55 years old, had survived assassination attempts, won impossible battles, and conquered Gaul. What was one more prophecy?

His wife Calpurnia had nightmares. She dreamed of holding his bloodied body in her arms, of a decorative pediment on their house torn down. She begged him to stay home on March 15.

Caesar hesitated. But Decimus Brutus, one of his generals and one of the conspirators, convinced him to go. The Senate was waiting. They might offer him something important.

On his way to the Senate, Caesar passed Spurinna and could not resist a taunt.

"The Ides of March are come," he called out. The danger period was almost over. He had survived.

Spurinna's reply was quiet: "Aye, but they are not gone."

The Murder That Killed the Republic

Sixty conspirators waited in the Theater of Pompey, where the Senate was meeting that day. About twenty had daggers. The others were there to block exits, distract guards, and provide political cover.

Caesar entered alone. Mark Antony had been delayed at the door by a conspirator who engaged him in conversation. Caesar's bodyguards waited outside.

The killing itself was chaos. They stabbed each other in the frenzy. Most of the twenty-three wounds were inflicted after Caesar had stopped fighting. Only one was fatal, a thrust to the chest.

He died at the base of Pompey's statue. His old rival watched in marble. You can read the full account of the Ides of March and what came after.

What Died With Him

The conspirators expected cheering. They emerged from the Senate waving bloody daggers, shouting that tyranny was dead and the Republic saved.

Rome locked its doors. The streets emptied. The liberators marched through a ghost city, proclaiming freedom to no one.

Within days, Mark Antony had turned public opinion with Caesar's funeral. He read the will aloud: money to every citizen, gardens opened to the public. He displayed the wax effigy with twenty-three wounds marked. He praised Brutus and Cassius as "honorable men" until the word became an insult.

The crowd burned Caesar's body in the Forum and went hunting for conspirators. They killed the wrong man first, a poet named Cinna mistaken for a senator with the same name.

Within three years, most of the sixty were dead. Brutus and Cassius fell at Philippi in 42 BCE, defeated by the combined forces of Antony and Octavian, Caesar's eighteen-year-old heir.

Within seventeen years, the Republic was formally dead. Octavian had eliminated all rivals and taken the title Augustus. The principate replaced the consulship. The emperors took the title Caesar as part of their name.

Cincinnatus had surrendered power because the crops would not plant themselves. Caesar held it until sixty senators decided he never would.

Both stories ended the same institution. But only one of them understood what it meant to give something back.

The Paradox of Competent Tyranny

Caesar's dictatorship poses an uncomfortable question: what happens when the tyrant is good at governing?

His calendar reform outlasted the Roman Empire by 1,500 years. His citizenship extensions laid the groundwork for a multicultural empire that would absorb Greeks, Syrians, Gauls, and Britons into a single political framework. His land reforms settled veterans who might otherwise have turned to banditry or revolution.

The Republic he destroyed had been failing for a century. The Gracchi brothers had been murdered for attempting reform in the 130s and 120s BCE. Marius and Sulla had marched armies on Rome before Caesar was born. The Senate had become an oligarchy of wealthy families who blocked any change that threatened their privileges.

Caesar fixed what the Senate would not fix. He did it by concentrating power that the Republic's founders had deliberately distributed.

The conspirators believed they were saving that Republic. They were not. The Republic was already dead, strangled by its own contradictions. Caesar had merely stopped pretending otherwise.

What came after Caesar was worse. The proscriptions of the Second Triumvirate killed more Romans than the civil war. The wars between Antony and Octavian lasted another decade. The empire that emerged was more autocratic than anything Caesar had attempted.

Brutus thought he was the new Lucius Junius Brutus, willing to kill what he loved to save something greater. But the first Brutus had built a republic. This one only dug its grave.

The Month That Bears His Name

We remember Caesar in July, the month named for him after his death. August came later, for Augustus. The pattern continued until September, which several emperors tried to rename but none could make it stick.

The Julian calendar he created remained the standard in the Western world until Pope Gregory XIII corrected a minor drift in 1582. Even then, the Gregorian calendar is essentially Caesar's system with a refinement to the leap year calculation.

Every time you check the date, you are using a system devised by a dictator who was stabbed to death for accumulating too much power. History has a way of honoring the things it claims to reject.

Cincinnatus is remembered too, but differently. The city of Cincinnati, Ohio takes his name. George Washington was compared to him when he surrendered command of the Continental Army and retired to Mount Vernon. The Society of the Cincinnati, founded by Revolutionary War officers, takes him as their model.

Both men held absolute power. One gave it back. One never would have. Both are essential to understanding what Rome was and what it became.

The Republic died because it could not decide which model to follow. Or perhaps because it produced too many Caesars and not enough Cincinnatuses.

The crops will not plant themselves. But neither will empires.

Frequently Asked Questions

1What reforms did Caesar implement as dictator?

Caesar reformed the Roman calendar (creating the Julian calendar still in use today), extended citizenship to conquered peoples, streamlined the court system, reduced the grain dole while settling citizens in new colonies, and began major construction projects including rebuilding Carthage and Corinth.

2What does 'dictator perpetuo' mean?

Latin for 'dictator in perpetuity' or 'dictator for life.' The Roman dictatorship was originally a temporary emergency office limited to six months. By making Caesar dictator perpetuo in 44 BCE, the Senate removed all time limits, giving him permanent absolute power.

3Who was Cincinnatus and why is he significant?

Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus was a Roman farmer made dictator in 458 BCE during a military emergency. He defeated the enemy in sixteen days, then refused all rewards and returned to his farm. He became the ideal of Roman virtue: power wielded briefly and surrendered willingly.

4What happened at the Lupercalia festival in 44 BCE?

Mark Antony publicly offered Caesar a royal diadem (crown) three times. Caesar refused each time to crowd applause. Ancient sources debate whether this was a genuine test of public opinion about monarchy or political theater designed to plant the idea while rejecting it.

5Why did Brutus join the conspiracy against Caesar?

Brutus was torn between personal loyalty to Caesar, who had pardoned and promoted him, and his family legacy. His ancestor Lucius Junius Brutus founded the Republic by overthrowing the last king. Anonymous notes reminded him of this heritage and pushed him toward assassination.

6What happened to the conspirators after killing Caesar?

Most were dead within three years. Public opinion turned against them after Mark Antony's funeral speech. Brutus and Cassius fled Rome, raised armies in the east, but were defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE, where both committed suicide.

Experience the Fall of the Republic

From Cincinnatus's farm to Caesar's throne, hear the story of how absolute power transformed Rome.

Listen to Related Stories

Key Figures

Listen to the Full Story

Experience history through immersive audio lessons narrated by Lumo, your immortal wolf guide.