The Morning Your Name Appeared

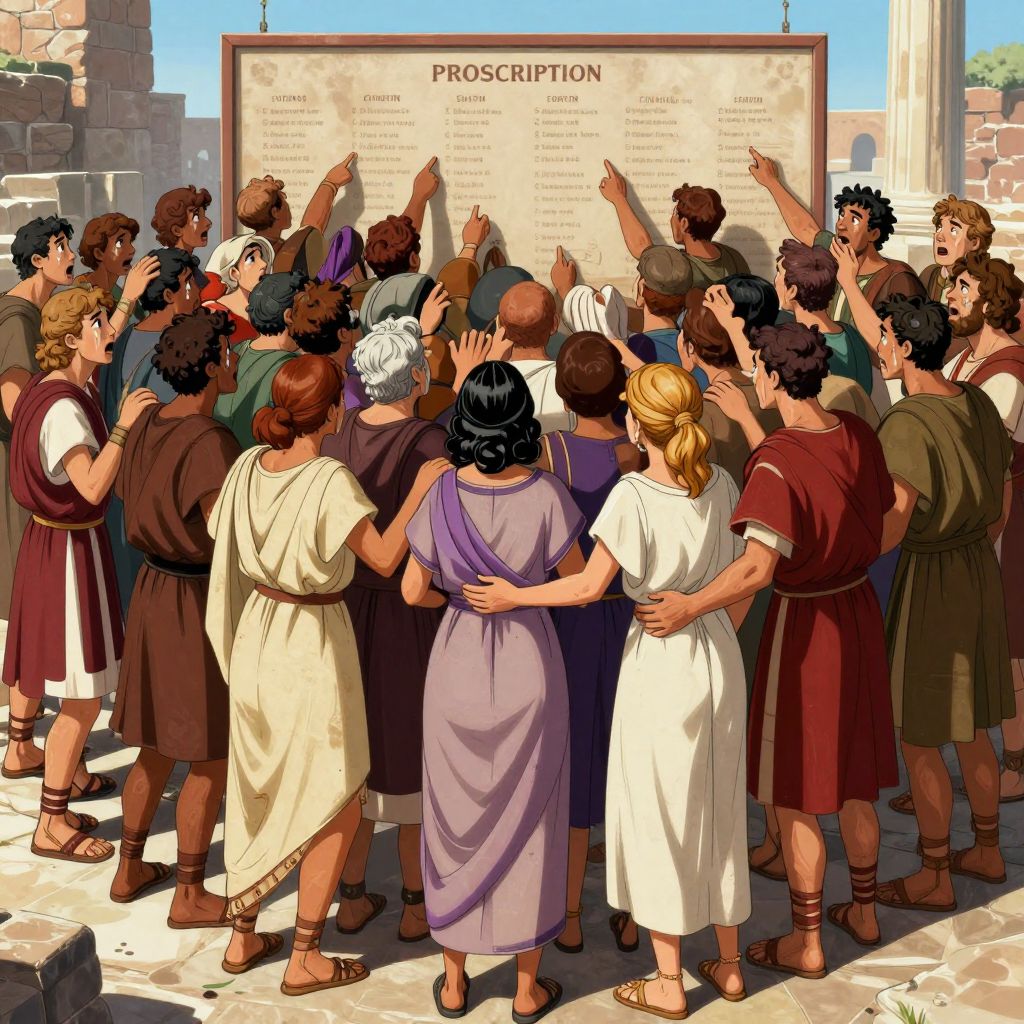

A man walked to the Forum one morning in 82 BCE to check the wooden board mounted on the stone wall. He found his own name halfway down the list. His hand went to his mouth. Then he turned and walked away, disappearing into the crowd, never to be seen again.

This was Sulla's innovation. Not the killing itself. Romans had been murdering each other in civil conflicts for decades. Gaius Marius had already shown that a returning exile could drown his enemies in blood. What Sulla invented was something far more insidious: he made murder bureaucratic.

The first proscription list appeared in the Forum with eighty names. Senators. Generals. Men who had backed Marius during the civil wars. If your name appeared, you were legally dead from that moment. Anyone could kill you and claim a reward. Your property went to the state. Your children were barred from holding office. Your family was ruined.

No trial. No defense. No appeal.

Then more lists appeared. And more.

The Return of the Dictator

To understand the proscriptions, you have to understand Sulla's return. In 88 BCE, he had marched on Rome, the first Roman general to turn his legions against the city. He had driven Marius into exile, reorganized the government, and then left to fight King Mithridates VI of Pontus, who had orchestrated the massacre of tens of thousands of Romans in Asia Minor.

Sulla spent four years fighting in the East. Behind him, Rome fell into chaos. Marius returned, supported by his ally Cinna, and unleashed five days of terror on Sulla's supporters. Senators were dragged from dinner tables and murdered in the streets. Marius died shortly after, raving and broken, but his faction held Rome.

By 83 BCE, Sulla had defeated Mithridates and signed a peace treaty. He turned his legions westward. Civil war erupted again, Roman against Roman, for the second time in a decade. The fighting was brutal. Sulla's forces won victory after victory, driving his enemies before him.

The decisive battle came at the Colline Gate in 82 BCE, just outside Rome's walls. Sulla's army crushed the last Marian resistance. Thousands of prisoners were taken. Sulla had them marched into the Circus Flaminius. The screaming lasted all afternoon.

He had won. Decisively. His enemies were dead or fled.

But Sulla was not finished.

The Mechanics of Murder

The proscription system was terrifyingly efficient. Wooden boards went up in the Forum, names painted in neat columns. The lists were public, updated regularly, posted for all to see. There was no hiding, no uncertainty about who was marked. If you could read, you could check whether you would live another day.

The bounty system created an army of informers and assassins. Anyone who killed a proscribed person could claim a portion of their property. Slaves who killed their masters received freedom. Children who reported their fathers received rewards. Everyone had a reason to kill.

Personal enemies made the lists. Business rivals appeared. People whose houses someone wanted found their names posted. Wealthy men with no political involvement at all were proscribed simply because their estates would enrich Sulla's supporters. Informers got paid for names, turning the system into a self-perpetuating engine of accusation.

Neighbors turned in neighbors. Friends hunted friends. Debtors found a way to cancel their obligations permanently. The fabric of Roman social trust, already frayed by years of civil war, shredded entirely.

Ancient sources provide varying estimates of the death toll. Appian claimed ninety senators and twenty-six hundred equestrians were proscribed, though later lists added many more. Modern historians put the total at several thousand. But the numbers almost miss the point. What mattered was the terror: anyone could die at any moment, for any reason or no reason at all.

The Young Man Who Almost Died

Among those marked for death was an eighteen-year-old aristocrat named Julius Caesar. His connections to Marius ran deep. His aunt Julia had been Marius's wife. His own wife, Cornelia, was the daughter of Cinna, Marius's ally who had ruled Rome during Sulla's absence.

Caesar went into hiding. He moved from house to house, bribing officials, staying one step ahead of the hunters. Eventually, prominent Romans pleaded with Sulla to spare the young man. They argued he was too young, too unimportant, too distant from the actual fighting to merit death.

Sulla agreed, but reluctantly. According to the ancient sources, he issued a warning that would prove prophetic:

"Spare him if you must. But mark my words: in that Caesar, there are many Mariuses."

They did not listen. They never do.

Caesar survived. He left Rome, served in the military in Asia Minor, and waited out the dictatorship. Fifteen years later, he would begin building the political coalition that eventually made him master of Rome. Thirty-three years later, he would cross the Rubicon with his legions, following the path Sulla had blazed.

The Dictator's Constitution

Sulla did not take power simply to murder his enemies. He had a political vision, one rooted in his aristocratic conviction that the Senate should dominate Roman government. The populist tribunes and demagogues who had risen over the past generation had destabilized the traditional order. Sulla intended to restore it.

He had himself appointed dictator, a constitutional office that had fallen into disuse. Unlike previous dictators who held power for six months at most, Sulla's dictatorship had no time limit. He held absolute authority to make laws and remake the state.

His constitutional reforms were extensive. He doubled the size of the Senate, filling it with his supporters. He stripped the tribunes of the people of most of their powers, preventing them from proposing legislation or vetoing senatorial decrees. He established minimum ages for holding each office, preventing ambitious young men from rising too fast. He required a ten-year gap between holding the same office twice, preventing the kind of repeated consulships that Marius had accumulated.

He packed the law courts with senators, removing the equestrian businessmen who had gained judicial power in recent decades. He established new permanent courts for specific crimes. He regulated the assignment of provincial commands, trying to prevent generals from building the kind of personal armies that had enabled his own rise.

The irony was not lost on contemporaries. Sulla used unprecedented violence to seize absolute power, then passed laws designed to prevent anyone else from doing the same. He broke every rule in the book, then rewrote the book to ban what he had done.

The Retirement

Then Sulla did something impossible.

He retired.

In 79 BCE, after three years as dictator, Sulla laid down his powers and walked away. He went to his villa in the countryside. He wrote his memoirs. He threw parties. He drank too much.

The ancient sources struggled to explain this decision. Why would a man who had seized absolute power voluntarily surrender it? Sulla himself seemed to view his work as complete. He had destroyed his enemies, rewarded his friends, and reformed the constitution. What remained was simply to enjoy the fruits of victory.

A year later, he was dead. Ancient sources variously attributed his death to intestinal disease, to liver failure from heavy drinking, or to an infestation of lice that consumed his body from within. The medical details are uncertain, but the basic fact is clear: Sulla died in his bed, surrounded by luxury, having faced no consequences for his crimes.

He wrote his own epitaph. It read: "No friend ever did him a kindness, and no enemy a wrong, without being fully repaid."

He meant it.

The Lesson Everyone Learned

Sulla's retirement might seem like a hopeful ending. The dictator stepped aside. The Republic continued. Normal politics resumed.

It was nothing of the sort.

Sulla had taught Rome a devastating lesson. You could seize power with an army. You could murder thousands of your enemies with legal impunity. You could rewrite the constitution to serve your interests. And then you could retire peacefully to the countryside and die of natural causes.

The generation that came after Sulla remembered what he had demonstrated. Pompey remembered when he demanded triumphs and consulships that the law denied him. Crassus remembered when he crucified six thousand of Spartacus's followers along the Appian Way. Most importantly, Caesar remembered when he stood at the Rubicon, weighing the decision that would plunge Rome into civil war again.

Sulla's constitutional reforms collapsed within a decade of his death. The tribunes recovered their powers in 70 BCE. Ambitious men found ways around the restrictions he had imposed. The Senate proved incapable of governing effectively without the tools Sulla had taken from it.

But the example lasted. Sulla had proven that force trumped law, that a loyal army could take anything, that proscription lists could wipe out entire political factions overnight. The Republic survived only because men believed its rules were legitimate. Sulla showed them that belief was optional.

The Shadow Over the Republic

The proscriptions cast a long shadow over Roman politics. For the next forty years, ambitious men plotted and planned, building armies and alliances, always with the knowledge that Sulla's path remained open to anyone ruthless enough to take it.

The Catiline Conspiracy in 63 BCE represented one attempt to follow Sulla's example. Catiline, a debt-ridden aristocrat, planned to seize power through violence, murder his enemies, and redistribute their wealth. Cicero exposed the plot and had the conspirators executed without trial, invoking emergency powers that echoed Sulla's proscriptions.

The Marian reforms had created armies loyal to their generals rather than the state. Sulla had shown what such armies could do when turned against Rome. The combination proved fatal to republican government. From 88 BCE onward, the question was never whether a general would use his army to seize power, but when, and which general would do it successfully.

Caesar's eventual dictatorship completed what Sulla had started. When Caesar took power after his civil war with Pompey, he pointedly refused to issue proscriptions, pursuing a policy of clemency instead, pardoning enemies who surrendered rather than murdering them. When Caesar was assassinated in 44 BCE, his heir Octavian joined with Mark Antony and Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate. Their first act was a new round of proscriptions, even more extensive than Sulla's.

Cicero, who had opposed the Triumvirate, found his name on the lists. The great orator who had crushed Catiline's conspiracy was hunted down and killed. His head and hands were displayed in the Forum where he had once spoken against tyranny.

The Price of Order

Sulla genuinely believed he was saving the Republic. He saw the populist tribunes and military strongmen of the previous generation as a sickness attacking the traditional Roman order. His proscriptions cut out the tumor. His constitutional reforms immunized the Senate against future infection. His retirement proved he wanted no permanent power for himself.

Of course, you could argue Sulla himself was the sickness. He introduced systematic political murder into Roman practice. He demonstrated that constitutional forms were meaningless against naked force. He enriched his supporters with the property of the murdered, creating a class of men with vested interests in maintaining his settlement.

The conservative aristocrats who supported Sulla believed that strong medicine was necessary to cure Rome's political sickness. They accepted the proscriptions as a temporary evil required for long-term stability. They thought order could be restored once the dangerous elements were eliminated.

They were wrong. Violence begets violence. The men who learned politics in Sulla's shadow learned that power came from swords, not speeches. The children of the proscribed remembered who had killed their fathers. The veterans who received confiscated lands knew their prosperity depended on keeping Sulla's party in power.

An Empire in Embryo

From the vantage point of the Empire, it's easy to see the proscriptions as the moment everything changed. Before Sulla, the Republic was troubled but functional. After him, it was a hollowed-out shell waiting for someone to push it over.

Augustus, the first emperor, would learn from both Sulla's successes and his failures. Like Sulla, he used proscriptions to eliminate enemies and reward supporters. Unlike Sulla, he did not retire. He understood that surrendering power created a vacuum that ambitious men would rush to fill. Better to hold power permanently, disguised in republican forms, than to step aside and watch the cycle begin again.

The Principate that Augustus created owed much to Sulla's example. The use of legal forms to disguise autocratic power. The elimination of potential rivals through quasi-judicial processes. The maintenance of senatorial dignity while stripping the Senate of real authority. All of these techniques appeared in Sulla's dictatorship before Augustus perfected them.

Sulla showed that the Republic could be seized. Augustus showed that it could be kept. Together, they authored the transformation of Rome from republic to empire.

Memory and Judgment

Roman historians struggled with Sulla's legacy. He was undeniably effective. He defeated every enemy, foreign and domestic. He reformed the constitution according to his principles. He retired voluntarily and died peacefully. By the standards of success in Roman political life, he achieved everything a man could want.

But the methods he used haunted Roman memory. The proscription lists became a symbol of tyranny, invoked whenever later leaders threatened to unleash similar violence. The phrase "Sullan times" served as a warning, a reference point for the worst possibilities of civil conflict.

Historians still argue about Sulla's place in the Republic's decline. He wasn't the sole cause. The social and economic forces transforming Roman society would have created instability regardless. But Sulla channeled those forces in devastating directions. He showed what was possible. More cautious men would have left those possibilities unexplored.

The Republic died slowly, over decades, through a series of civil wars and political crises. But if we look for a moment when death became inevitable, Sulla's proscriptions have a strong claim. The lists that went up in the Forum in 82 BCE announced that the rules had changed. Violence had become administrative. Murder had become policy. The old Republic, whatever its flaws, was gone forever.

Frequently Asked Questions

1What were Sulla's proscriptions?

The proscriptions were formal death lists posted in the Roman Forum starting in 82 BCE. Anyone whose name appeared could be legally killed by anyone, with the killer entitled to a portion of the victim's property. The system included bounties for informers, rewards for slaves who killed their masters, and complete confiscation of the deceased's estate. The first list contained eighty names, but subsequent lists added many more.

2How many people died in Sulla's proscriptions?

Ancient sources provide varying estimates. Appian claimed ninety senators and twenty-six hundred equestrians were officially proscribed, with later additions bringing the total higher. Modern historians estimate several thousand deaths overall, including both those formally proscribed and victims of the subsequent chaos and personal vendettas.

3Why did Sulla retire voluntarily?

Sulla apparently believed his work was complete. He had eliminated his enemies, rewarded his supporters, and reformed the constitution to prevent future populist challenges to senatorial authority. Unlike later dictators, Sulla seemed genuinely uninterested in holding power for its own sake. He viewed his dictatorship as a temporary measure to restore proper order.

4How did Julius Caesar survive the proscriptions?

Caesar's connections to Marius through marriage made him a target. He went into hiding, bribing officials and moving between safe houses. Eventually, influential Romans interceded on his behalf, and Sulla reluctantly agreed to spare him, reportedly warning that Caesar contained many Mariuses within him.

5What was Sulla's epitaph?

Sulla composed his own epitaph, which read: 'No friend ever did him a kindness, and no enemy a wrong, without being fully repaid.' This captured his self-image as a man who rewarded loyalty and punished opposition with equal thoroughness.

6Did Sulla's reforms last?

Most of Sulla's constitutional reforms were dismantled within a decade of his death. The tribunes recovered their powers in 70 BCE under the consulship of Pompey and Crassus. The age and term limits he imposed were routinely circumvented. His attempt to strengthen the Senate failed because the underlying social and economic forces driving Roman instability remained unaddressed. What lasted was his example of using military force to seize and reshape the state.

Experience the Full Story

Hear Sulla's rise and the Republic's fall told by an ancient witness who watched the lists go up.

Listen to Related Stories

Key Figures

Listen to the Full Story

Experience history through immersive audio lessons narrated by Lumo, your immortal wolf guide.